Amid steeply escalating school crime, drug use and fighting, individual Los Angeles public school campuses should be allowed to decide whether to station a police officer on campus, a safety task force said, a recommendation that, if adopted, would reverse wins by anti-police student activists but respond to calls by many parents to restore officers.

Recent practice in the L.A. Unified School District has been to keep police off campus. Instead, school police — a department paid for and operated by the school system — patrol areas around schools and respond to emergency calls off and on campus.

The task force, established by the Board of Education, has operated quietly during the current school year against a backdrop of rising fights on campus and difficulty controlling vaping and the use of serious drugs, such as fentanyl, which killed a student on campus in 2022. District data show a sharp rise in what the school system refers to as reported incidents.

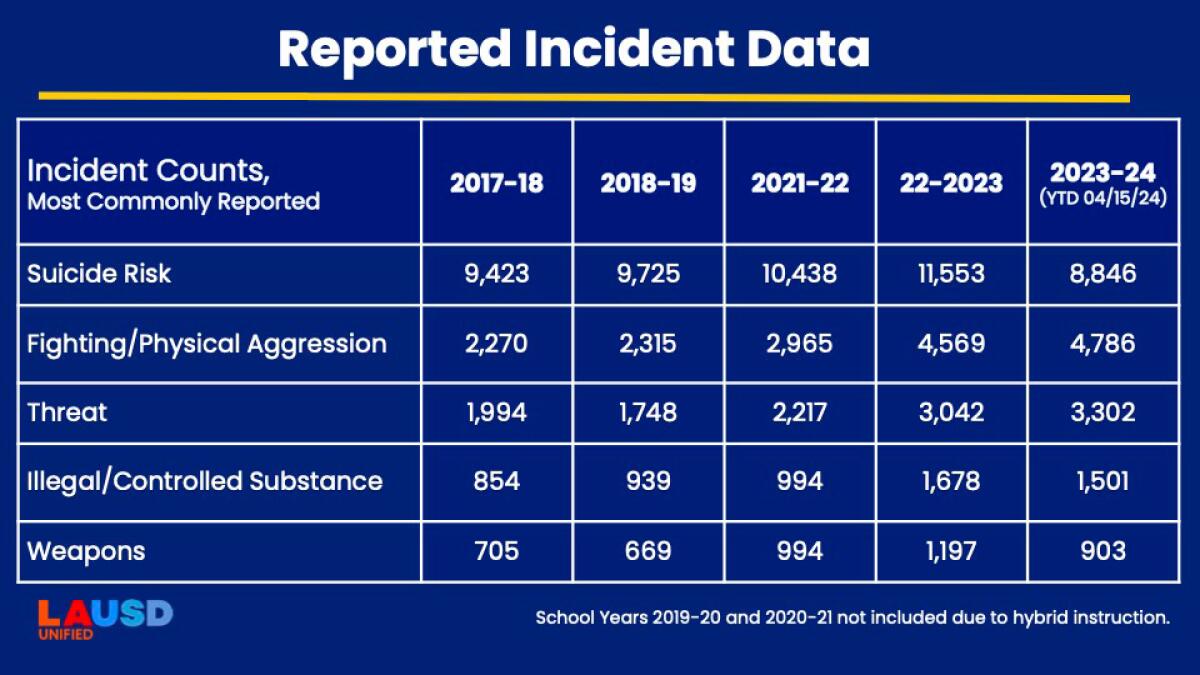

The latest data leave out the two peak-pandemic years of 2019-20 and 2020-21 because students were learning from home for all or much of the time. But with that caveat, incidents under “Fighting/Physical Aggression” have climbed every year since 2017-18, despite declining enrollment. Incidents especially surged once students returned from remote instruction.

Before the pandemic, in 2017-18, there were 2,270 such incidents; the next year, also pre-pandemic, recorded a 2% rise to 2,315. Then came the pandemic and remote learning. After on-campus instruction resumed, these incidents increased 28% in 2021-22 and by 54% year over year in 2022-23.

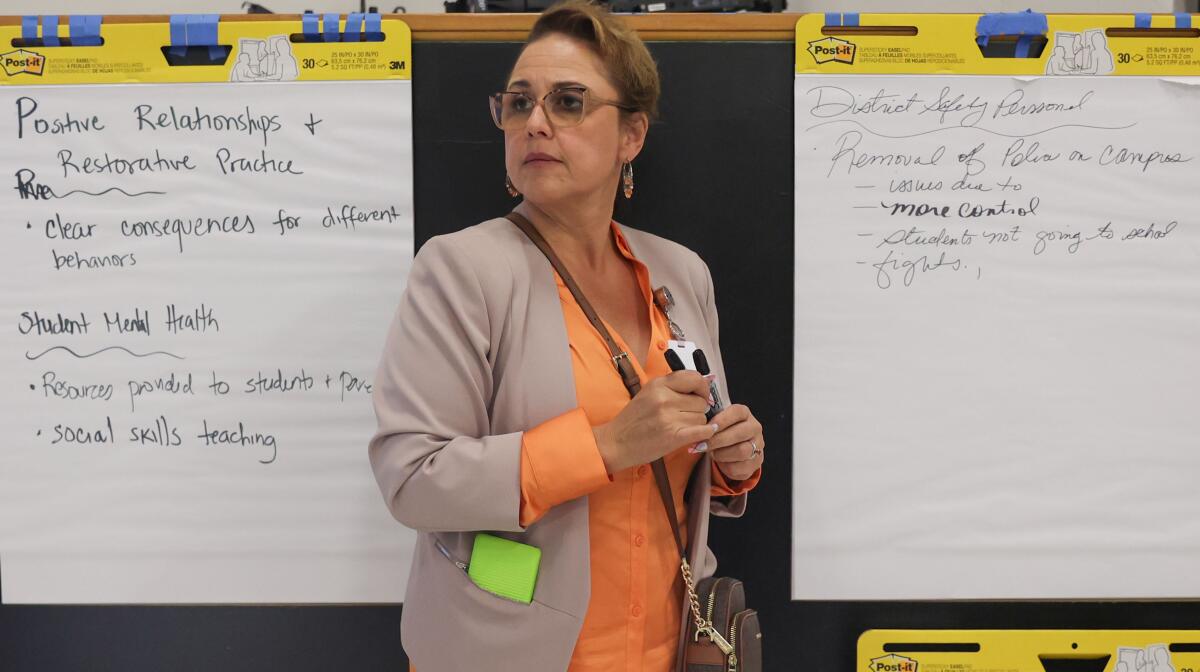

Brenda Fernandez, an LAUSD staff member, listens in between writing down notes from parents concerned about school safety during a meeting May 2 at Patrick Henry Middle School.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

Put another way, during the two full years since police were removed from campus, incidents of fights and physical aggression rose to 4,569 from 2,315, almost doubling. And as of April 15, with about two months left in the school year, the number was higher still — at 4,786.

It was on April 15 that tension at Washington Preparatory High School in South L.A. boiled over in an after-school confrontation a few blocks from campus. A student fending off at least five other students pulled out a gun and opened fire. A 15-year-old died.

In that incident, a nonpolice school-safety worker, part of the “safe passages” program, allegedly declined to intervene when approached by students just before the fight began.

“One student died because safe passages does not work,” said Diana Guillen, a leader on a key district parent advisory council. She said a parents group is going to have at least 2,000 signatures calling for a restoration of school police to present to the Board of Education at Tuesday’s meeting, when the task force’s recommendations will be presented.

The school board is not expected to take immediate action, but L.A. schools Supt. Alberto Carvalho is developing a revised safety plan, part of which may require the board’s authorization.

At an April meeting of the Board of Education, more than two dozen parents called for increased police staffing and the return of officers to campuses.

A chart from a Los Angeles school board committee meeting in April indicates that incidents among students involving suicide risk, fighting, weapons and illegal/controlled substances have risen steeply since students returned to in-person instruction after pandemic campus closures.

Any member of the public could participate in the task force, but most involved appear to have been district employees — including within the school police — as well as community members and parents who are not anti-police. The outgoing head of the school administrators union, Nery Paiz, also took part. No anti-police activists attended the task force’s April meeting.

Anti-police student activists and professional organizers working with them are likely to have a presence Tuesday at the Board of Education meeting. They typically have speakers at board meetings at least once a month and stage rallies at least twice a year. The anti-police effort also is backed by the leadership of the politically influential teachers union, United Teachers Los Angeles.

Anti-police activists successfully advocated for pushing officers off campus during the Black Lives Matter protests that peaked after the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis city police. That board action, by a 4-3 vote in June 2020, also slashed the police budget by 35%.

Although celebrating that action, activists wanted more — the complete elimination of school police — and are angry at what they see as broken promises and backsliding: The school police budget has crept upward, pulled along by districtwide salary increases and higher costs. Overall, police staffing remains at a reduced level.

Before the cuts, a high school typically would have one full-time officer and two middle schools would share one officer.

In the recently released data, the categories of “suicide risk” and “illegal/controlled substances” also showed small rises in the last year of the on-campus police presence — suggesting that all was not well even with officers assigned to schools. But as with the fighting, during the 2021-22 and 2022-23 school years, the district experienced sharp rises in the number of incidents.

In two categories, threats and weapons, the numbers were lower in 2018-19 but then rose over the last two years.

Cause and effect related to school police is difficult to determine because so many factors are at play. Student mental health issues, for example, worsened across the nation in the wake of the pandemic and there were widespread — largely anecdotal — reports of increased campus fighting. It’s hard to know the extent to which the L.A. Unified data reflect the lack of police, post-pandemic stresses or other factors.

It’s also hard to evaluate the consistency of incident reporting. The school system has long refused to release even redacted incident reports that would permit an independent assessment. Nor will the district release information about incidents in relation to specific campuses.

Marcos Tapia holds a card for the school safety meeting at Patrick Henry Middle School on Thursday, May 2, 2024, in Granada Hills.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

Last year, student activists at Dorsey High in South L.A. said that they felt safer, more respected and better able to focus on coursework thanks to the removal of the school’s police officer and the addition of more counselors.

Last week, more than 100 parents attended a school safety town hall at Patrick Henry Middle School in Granada Hills. At this meeting, parents called for more police, but also acknowledged the complexity of the problem.

Several parents focused, for example, on what they said was ineffective behavior management by school staff, poor communication with families and the district policy to avoid student suspensions. Parents complained that children were being bullied and beaten — only to see the perpetrators continue at school and in their classes as though nothing had happened.

Avoiding suspensions is not meant to be the same as avoiding consequences. Ideally, students who are acting improperly are counseled and taught to take responsibility for their actions and to make things right through a “restorative justice” process. This is widely viewed as an alternative to heavy-handed discipline and suspensions that can interfere with learning and increase the number of dropouts.

But the uniform success of restorative methods has been called into question even by school board President Jackie Goldberg, who strongly supports these reforms in concept.

Carvalho said the safety dynamic is more nuanced than simply pro-police or anti-police.

“Good systems understand the culture within schools — are able to anticipate and solve some of these issues before they happen,” he said. “It’s about supervision. It’s also about engagement with parents. It’s also about providing kids an opportunity for outlets within their own communities.”

“We need to go deeper,” he said. “It cannot just be pro-police or against police. That is not an approach that alone will solve the issue.”