Table of Contents

The two men lay on the sidewalk of a darkened street in Lomita.

One carried a gun he’d had no opportunity to use. The other was tattooed with symbols of the Russian underworld. Both had been shot a single time in the head.

Neither Allan Roshanski nor Ruslan Magomedgadzhiev had ties to 255th Street, where sheriff’s deputies found their bodies at 1:30 a.m. one Sunday in 2020.

The mystery deepened when federal prosecutors charged two reputed members of the Aryan Brotherhood, a crime syndicate of white inmates, with ordering their murders from a prison hundreds of miles away.

Prosecutors haven’t revealed how they believe two men with ties to Russian and Israeli organized crime circles collided with two alleged prison gang leaders. But through a review of court and prison records, The Times traced their paths to the night of the killings.

Each had his own dark past: The pimp. The strong-arm for an Israeli mob. The “polite” inmate who tried to kill a deputy. The teenage murderer who cut out part of an informant’s tongue.

Mob tattoos, escorts and a ‘trap house’

Roshanski, 36, had been shot behind his left ear. Beneath his jeans and Puma sweatshirt, a coroner’s investigator noted tattoos: Stars on the knees. Four dots on the back of the left hand, with a fifth dot in the middle.

His markings are significant in Russian prison culture, an organized crime figure who served time in the Russian penal system told The Times. The source, who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation, said the hand tattoo was a common mark of a prisoner. The four dots represent walls; the fifth, the inmate constrained by them.

But the stars on the knees, which signify a refusal to kneel before authorities such as police or judges, could be worn only by high-ranking Russian convicts, the source said. Roshanski had done prison time — but in California, and for crimes that didn’t suggest the profile of an upper-echelon criminal.

Roshanski served a year for pimping women in Hollywood. According to a case brought by Los Angeles County prosecutors, he advertised the women’s services on the website Backpage, negotiated prices and booked hotel rooms where they met clients. In exchange, one woman told police, Roshanski took 20% to 30% of her earnings.

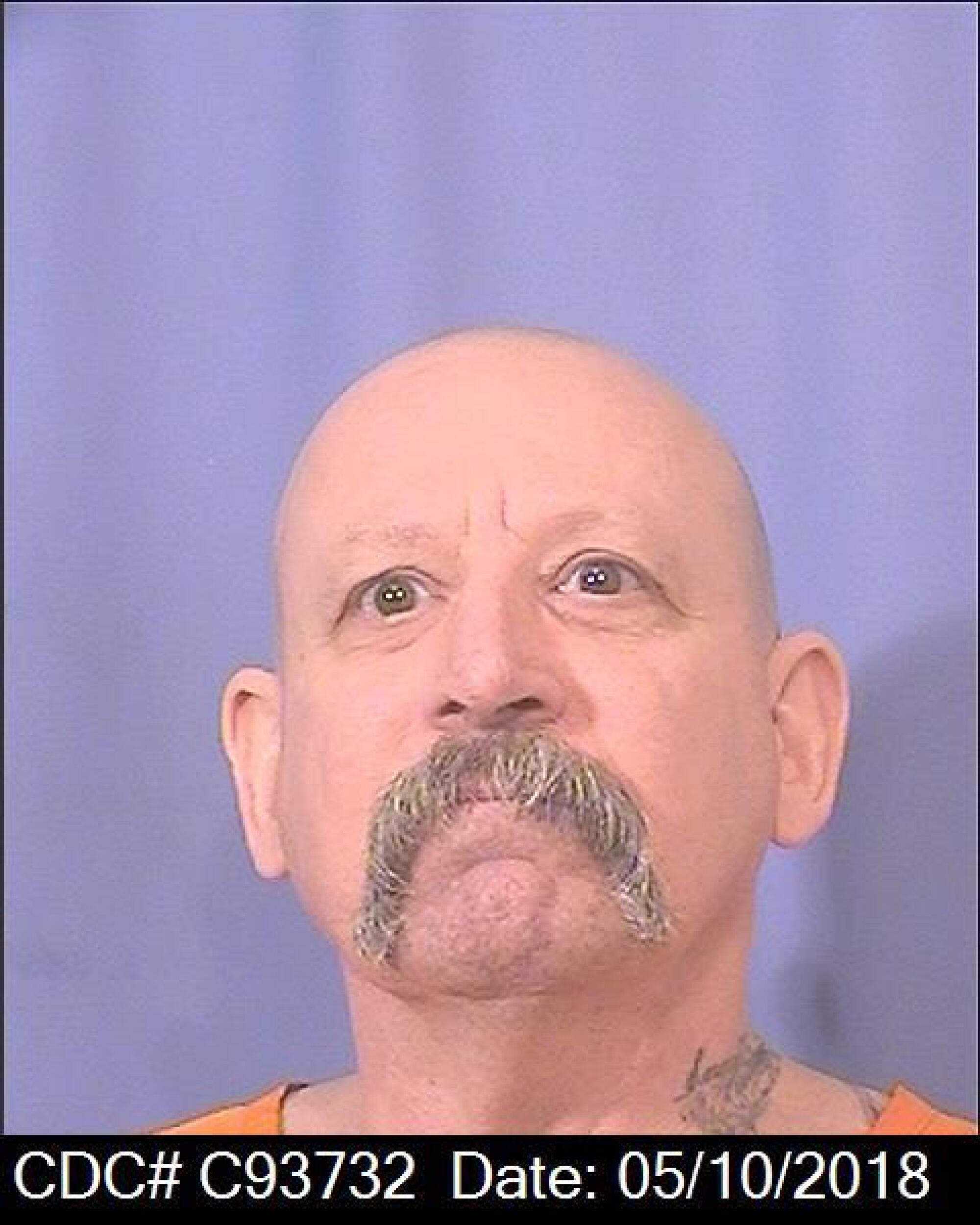

Allan Roshanski, shown here in a 2017 photograph from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, was killed on Oct. 4, 2020.

(California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation)

In 2020, two years after leaving prison, Roshanski told a friend that some of his property had been stolen while he traveled to see his mother in another state, according to a search warrant affidavit.

The day before he died, Roshanski told the friend he’d gotten a call from someone who had his “stuff.” He needed to go to a “trap house” — a property where drugs are sold — in Long Beach.

Roshanski, his friend said, “appeared very nervous, which is out of character for him,” the detective wrote in the affidavit. He called another friend and told him “he had something to do and needed him to cover his back.”

The friend was Magomedgadzhiev.

A botched ambush in Vegas

In 2008, two Israeli businessmen in Las Vegas fell out with a partner, Yakov Cohen, over allegations he was embezzling from their chain of kiosks that sold cosmetics in outlet malls.

In an attempt to force his partners to buy him out, Cohen turned to Moshe Barmuha, described in a federal agent’s affidavit as an Israeli organized crime figure whose right arm had been amputated at the elbow after a pipe bomb he was trying to place under a car exploded prematurely.

Threatening phone calls and notes left on doorsteps failed to persuade the businessmen to pay, the affidavit said. Looking to hire some muscle, Barmuha was introduced to Magomedgadzhiev through his boss at a moving company in Tarzana.

Having served in the Russian military and trained as a boxer, Magomedgadzhiev told the police he “knew how to do things,” although his recent work had been more mundane. He had studied accounting in his native Chechnya before immigrating to Los Angeles around 2001, he wrote in a letter to a judge. He worked as a golf course landscaper and later as a trucker and mover.

Magomedgadzhiev said Barmuha gave him $200 and a phone number to call once he reached Las Vegas. “Make the guy know that if he [doesn’t] pay up,” Barhuma said, according to a police report, “things would not be nice like they are now.”

Magomedgadzhiev and his brother met Cohen at a casino and followed him to an apartment complex, where he pointed out an Infiniti coupe.

The brothers waited and watched. A man unlocked the Infiniti. They ambushed him, throwing him against the car and striking him in the head, the brothers admitted in plea agreements.

Knocked to the ground, the man drew a gun and started shooting. Magomedgadzhiev was hit in the buttocks and the calf. Afraid to go to a local hospital, his brother drove him to one nearly 300 miles away in Tarzana, where they made up a story that he’d been shot in a drive-by.

After pleading guilty to traveling across state lines in aid of racketeering, Magomedgadzhiev spent two years in federal prison.

The Aryan Brotherhood’s alleged hitman

Sheriff’s detectives, surveying the dark street in Lomita, were baffled. Magomedgadzhiev had a Tarzana address; Roshanski was last known to be living in near San Diego.

“It remains unknown why they were at the location and who they were there to meet,” a detective wrote in a search warrant affidavit.

A month later, they got a call from an LAPD narcotics officer. An informant claimed to have overheard a man named Justin Gray saying he’d “got those two Russian guys” in Lomita. According to the source, Gray had been promised membership in the Aryan Brotherhood in exchange for the killings.

Justin Gray, shown in a 2022 photograph from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, is charged with murdering two men in Lomita in 2020. He has pleaded not guilty.

The informant provided a phone number for Gray. Records showed that Roshanski had called Gray’s phone three times in the hour before he was killed, according to the affidavit.

A federal grand jury in Fresno indicted Gray on murder charges in 2023. Accused of ordering the hits were two reputed members of the Aryan Brotherhood, Kenneth “Kenwood” Johnson and Francis “Frank” Clement.

Along with the killings in Lomita, Clement is charged with ordering a murder in 2022 and a double-homicide two weeks later in Pomona. Johnson and Clement are also accused of orchestrating yet another murder in 2016.

Gray, Johnson and Clement have pleaded not guilty. Lawyers for Gray and Johnson didn’t return requests for comment. Clement’s attorney declined to comment.

The indictment reveals no motive. Prosecutors haven’t said how they connected two longtime prisoners to killings hundreds of miles away.

The polite inmate who lived in a ‘homicidal society’

Through his attorney, Johnson has denied directing the murders alleged in the indictment. But the 63-year-old was candid before the parole board about living in what he called a “homicidal society” behind prison walls.

“Everybody in here, almost 90-something percent in any [high-security] prison, are all murderers or pretty close to it,” he said. “Violence is part of the environment, like it or not. And even if you don’t want to be involved in it, it’ll find you one way or another.”

Raised in San José, Johnson was arrested for burglary as a teenager and spent 14 months at a youth ranch, according to parole records. As an adult he racked up convictions for robbery, assault, receiving stolen property and possessing guns as a felon.

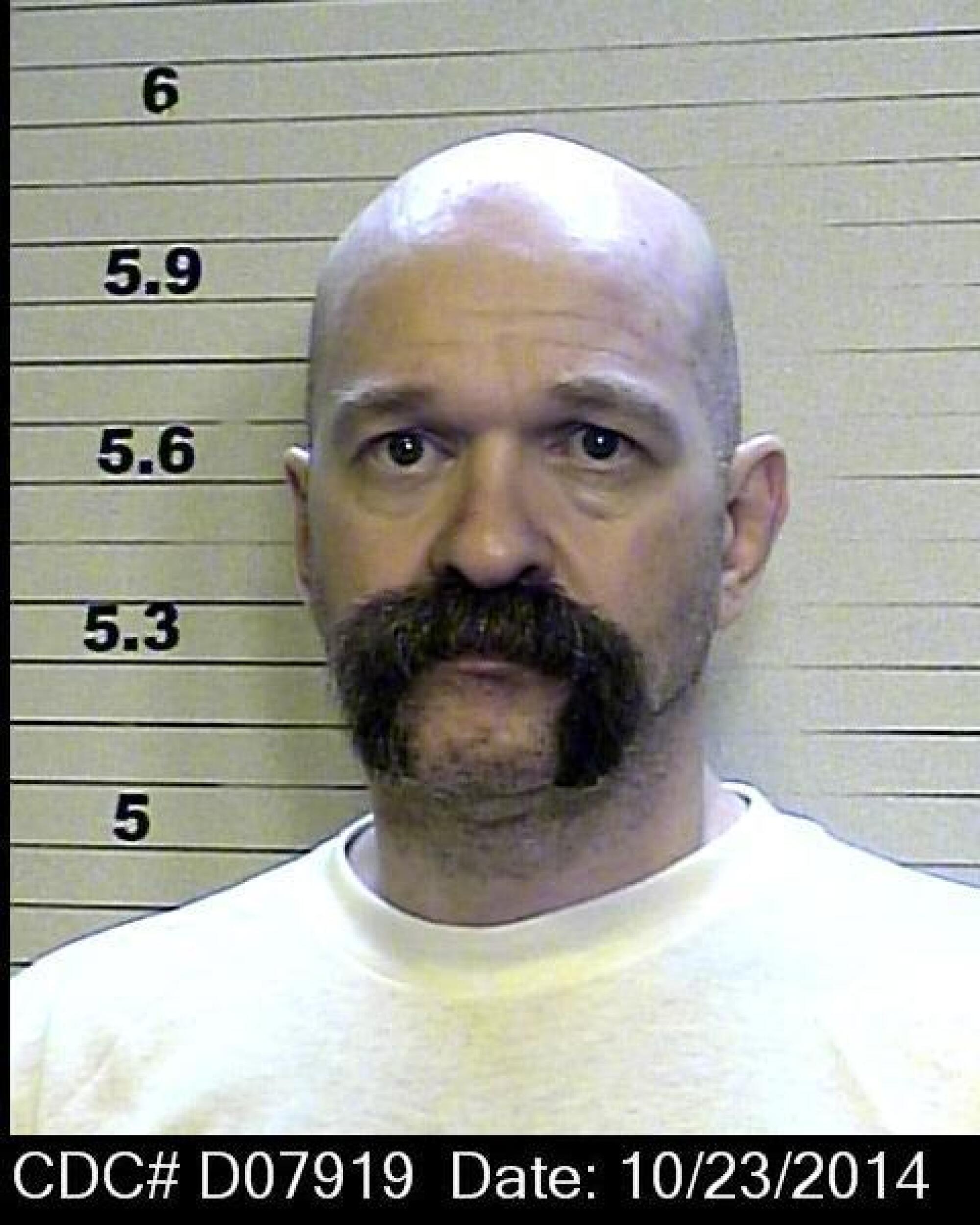

Kenneth Johnson, shown in a 2018 photograph from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, is charged with ordering a double homicide in Lomita in 2020. He has pleaded not guilty.

(California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation)

When he was out of jail, Johnson told the board, he repaired boats and cars as a certified Volvo mechanic.

In 1994, Johnson was living in the mountains of eastern Madera County. While drunk and high on methamphetamine, he got in a fight with a friend. A woman called the Sheriff’s Department.

Johnson fled. He climbed a fence into a back yard and shot a collie-shepherd mix, then hid behind a bush. When a sheriff’s deputy approached, Johnson fired at him four times. The deputy, who wasn’t hit, shot Johnson in the arm.

Convicted of attempted murder and cruelty to an animal, Johnson was sent to the maximum security prison at Pelican Bay. Authorities classified him as an affiliate of the Aryan Brotherhood — an allegation he denied at parole hearings.

Held for years in solitary confinement, Johnson told the board he read the Wall Street Journal cover to cover five days a week. A psychologist who examined Johnson found him an “engaging” person, “polite and straightforward,” according to parole records.

But in denying Johnson parole in 2010, a commissioner said he was concerned by the inmate’s view of violence. He didn’t resort to it on impulse, he wrote in a letter to the board. “Sometimes it was used as a tool, be it a threat, implied threat or actual use of it. A means to an end.”

‘It’s the living dead’

Violence was something Clement understood from a young age.

Raised in Springfield, Ore., Clement told the parole board he grew up picking strawberries and beans on his family’s small farm. When he was 12, his father came home from serving a prison term for burglary. Clement recalled his father was “mean” and often beat him.

The day before he turned 18, Clement and a friend, Charles Murphy, left Oregon for Las Vegas. They stopped in Sacramento, where they spent the night at a motel swimming with two teenage girls and getting “loaded” on Jack Daniels, methamphetamine, acid and marijuana, Clement said.

Murphy and one of the girls left the pool first. When Clement returned to the room, he told the board, he found Murphy raping her. He took a knife from his pocket and cut his friend’s throat.

Francis Clement, shown in a 2014 photograph from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, is charged with ordering a double homicide in Lomita in 2020. He has pleaded not guilty.

A year after being convicted of Murphy’s murder, Clement entered the prison cell of a man rumored to be an informant, announcing he was going to “kick a snitch’s ass.” After trussing the man to his bed, Clement slashed his stomach with a razor blade, slit his throat and cut out part of his tongue.

Clement said it was wrong to hurt the man, who survived, but being “thrown into a violent and chaotic world” at a young age, he “did things to survive.”

Like Johnson, he was sent to Pelican Bay and linked by prison officials to the Aryan Brotherhood. “I deny any involvement with any gang, prison gang, period,” Clement said.

Nor, he said, was he directing crime on the streets. Men like him, locked up for decades with no expectation of getting out, were not part of the same world as people outside prison.

“In here it’s the living dead,” he told the board. “You’re not living at all.”