Your support helps us to tell the story

As your White House correspondent, I ask the tough questions and seek the answers that matter.

Your support enables me to be in the room, pressing for transparency and accountability. Without your contributions, we wouldn’t have the resources to challenge those in power.

Your donation makes it possible for us to keep doing this important work, keeping you informed every step of the way to the November election

Andrew Feinberg

White House Correspondent

When Paige Cognetti first ran to become mayor of Scranton, she was told she couldn’t win because she did not have an Irish last name. She also had to overcome the fact that no woman had held the position in the city’s history.

Her victory in a special election in 2019, and again two years later, was seen by many as a sign of shifting tides.

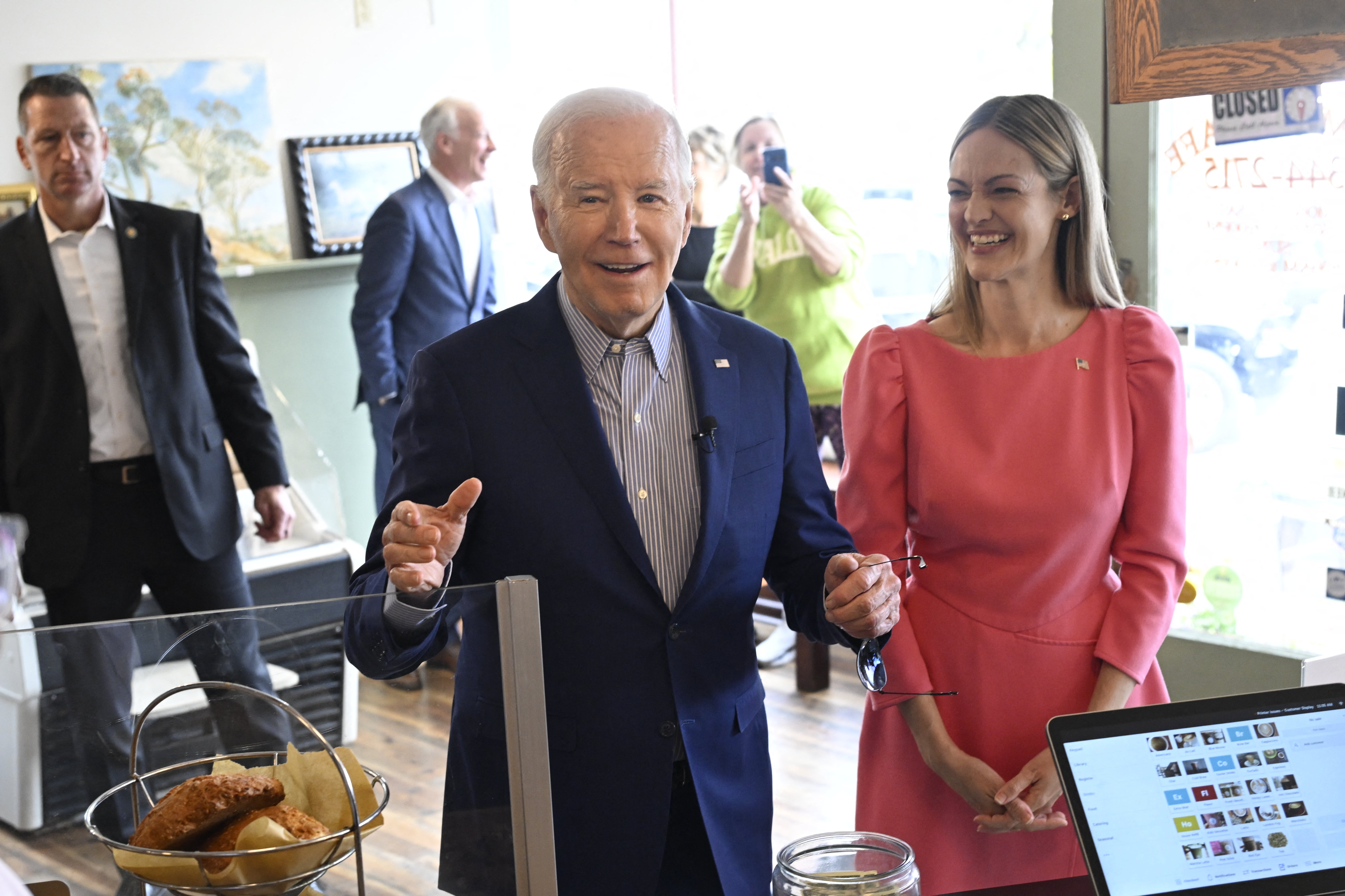

“There were a lot of factors against me,” she says over coffee at Abe’s Deli, in the center of the town. “But I think it was pretty clear that the city needed a change candidate,” she adds.

Kamala Harris visits the area on Friday to try to win over the same kind of voters that helped Cognetti win in this key city in the swing state of Pennsylvania. Donald Trump was also there last month. It is no exaggeration to say that her path to the White House runs through these streets.

There may be lessons in Cognetti’s story for the Harris campaign. The challenges that Cognetti faced then are similar to those that Harris faces now.

“When you run for office, especially as a woman, any number of people will try to convince you not to. Whether it’s questioning your gender, your heritage, your race, or your experience, some folks will attempt to tear you down so that you either don’t run or lack confidence while you do,” Cognetti says.

“We are seeing this in real-time with people second-guessing and nitpicking VP Harris while giving a pass to Trump as he continues to implode,” she adds.

That second-guessing has been particularly prominent in Scranton.

Joe Biden was born here in the city and he used the story of his difficult upbringing to win those kinds of voters across the state. It enabled him to connect with white working-class voters that Trump captured so comprehensively in 2016, and pull away just enough to win him the White House. Today a main street that runs through the center of the town is named after him.

Harris’s “Scranton problem,” as it has been dubbed, suggests that she may not be able to repeat Biden’s success here, and her chances of winning the state — and the presidency — are diminished as a result.

But Cognetti’s story may provide an answer to that question.

Like Harris, she is an outsider to Pennsylvania. She was born in Eugene, Oregon, studied at Harvard University, and went on to join the Treasury Department under Barack Obama’s administration.

Part of her pitch when she ran for office was that she was a technocrat — someone who could balance the budget and run the city’s finances responsibly after her predecessor was charged with corruption.

Pennsylvania has never elected a woman as US Senator or governor. But before Cognetti, Scranton had never had a woman mayor.

Cognetti was involved with both of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaigns and saw the misogyny she faced up close.

“I think that in America we still have a problem with women in leadership. I am one, and I know how much flack I take from various little pockets of the internet and the continued microaggressions” she says.

”Sometimes you look back and you think that a vote for Trump in 2016 was this kind of stick it to the establishment or stick it to something. My worry in 2016 was that a lot of it was this undiagnosed dislike of women. I hope we don’t see that again in 2024,” she adds.

There are other changes happening in Scranton that may help Harris.

“It is still very much a working-class community. And there are lots of folks that are either current or former union workers, former factory workers, generations of folks where the men in their family worked in the mines,” she says, “but we’re also a city that’s rapidly diversifying.”

Just ten years ago the city was 80 per cent white; today that has dropped to 68 per cent. That diversity is visible across the city today.

“We’re doing more festivals — in addition to our La Festa Italiana and the St. Patrick’s parade, there’s Latino Fiesta in August. We have a big Juneteenth celebration in June. There’s any number of new festivals to add on to the ones that we have had,” Cognetti says.

These changes may offer some hope to a campaign with a change candidate like Harris, which may aim to rely less on white working-class voters than previous generations of white male candidates.

Harris may not win the same number of white working-class voters as Biden here, but she is outperforming him among the ever-increasing number of Black and Latino voters.

The Harris campaign is going after those voters with renewed vigor. It announced a new Spanish-language ad in Pennsylvania on Friday aimed at the state’s 579,000 eligible Latino voters.

The ad features Victor Martinez, the owner of Pennsylvania’s largest Spanish-language radio network and a popular morning show host.

“They all talk. The difference is Kamala Harris listens,” he says in the ad.

In short, the Scranton that exists in the public imagination has not yet caught up with the real-life city today.

The city was once an industrial hub known as the «Anthracite Capital of the World” for its prodigious output of anthracite coal mines.

It earned its nickname, the Electric City, from the creation of the first trolley system to run solely on electric power.

The town prospered and grew, and out of that success came a powerful labor movement.

In front of the county courthouse stands a statue of John Mitchell, another hometown hero and former president of the United Mine Workers of America, who led huge strikes and battled to win an eight-hour workday and minimum wage for his members in the early 20th century.

However, as industry declined across the US, so too did Scranton.

Today, its population is only half of what it was at its peak in the 1930s, when some 143,333 people called it home.

That flight of people gave Scranton a reputation as an emblem of post-industrial decline. It later became the setting of the popular sitcom The Office — chosen for its supposed humdrum personality. The original UK version of the show is set in Slough, a town once named Britain’s “worst place to live.”

But today the city hosts a lively restaurant scene, and new coffee shops bustle with college students. The city hall is being repaired in part with money from the Biden administration’s infrastructure investment.

It is that investment, and Harris’s plan to improve the economic lives of people in Scranton, that Cognetti believes can help her win here.

“We could spend all day talking about foreign policy and abortion and the Senate, everything, but people care if can they afford this cup of coffee and this breakfast sandwich. Can they afford to take their family off to breakfast on Sunday morning after church?” she says.

“I don’t think that’s a Pennsylvania or a Scranton thing. I think that’s just a human desire. But that’s what we need to always be focusing on.”

But Harris does not have to completely ignore the constituency that Biden won here, Cognetti says. Having two old Midwestern white guys on her team counts for a lot.

“She has his story in that she’s Joe Biden’s vice president. She not only has his support now as a presidential candidate, but she was who he tapped four years ago to be his vice president.

“Also Tim Walz as the VP candidate is a helpful presence on the ticket in places like Northeastern Pennsylvania. He’s a guy that you could walk into Home Depot and ask to show you the light bulbs.”

Republicans are outnumbered in Scranton, even if they dominate in the rural areas that surround it. Across town at the local Republican Party office, currently serving as a Trump campaign headquarters, Linda Bonczkiewicz is skeptical Harris can repeat Biden’s success. “I’m giving every penny, every moment of my time to this campaign,” she says, surrounded by Trump yard signs and vote registration sign-up sheets in the office.

“I don’t like anything she has done. She has been in office for three and a half years and she hasn’t done anything. So what more is she going to do as president?” says Bonczkiewicz, who was raised on a farm and now lives in a rural part of Lackawanna County.

Bonczkiewicz says Democrats have come into the office to switch their party registration to Republican — something that is borne out by the official statistics.

But nonetheless, the margins in Pennsylvania remain razor-thin.