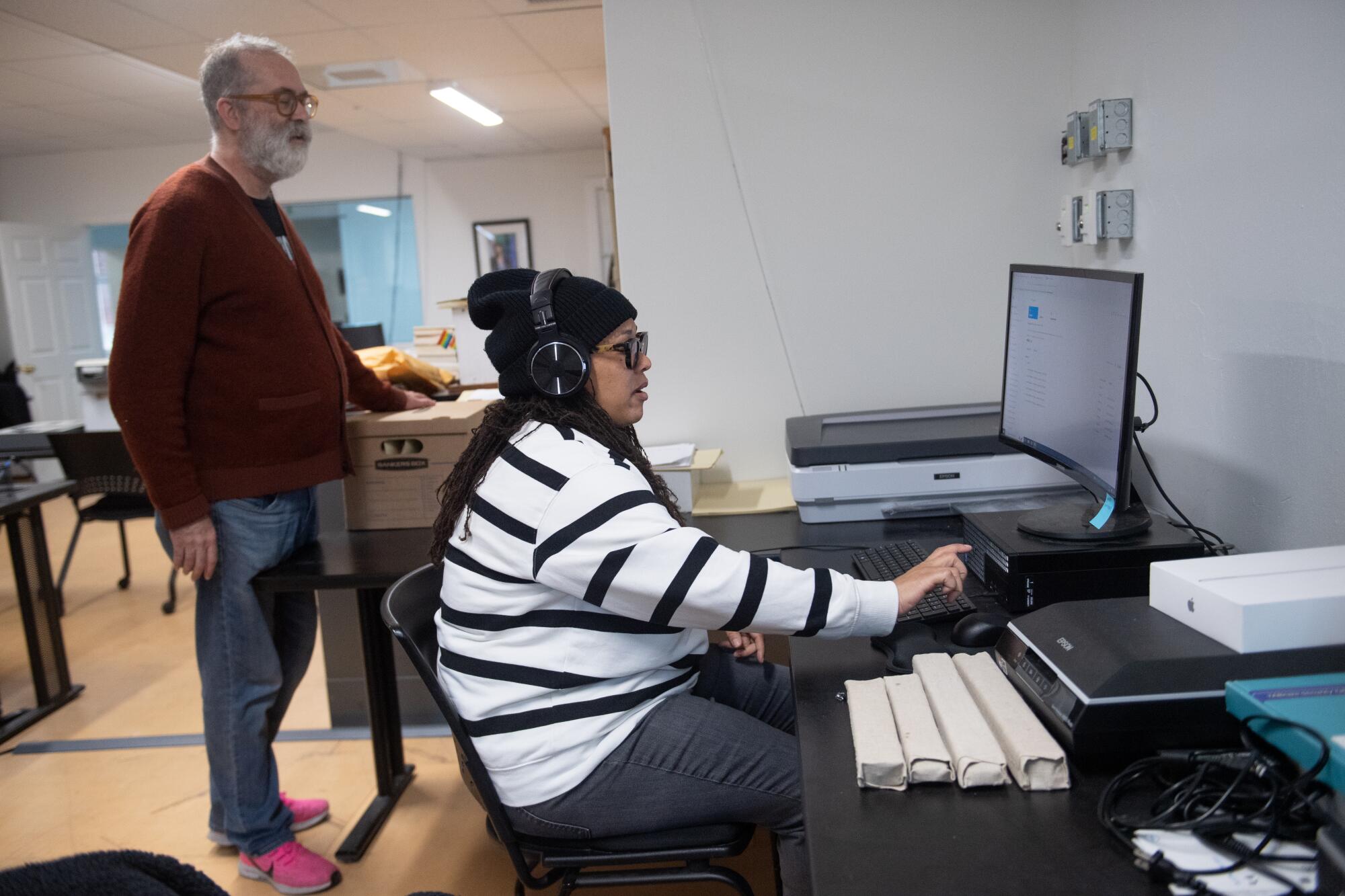

When I was 33 years old, I realized I was a coward. It came all at once, like a punch to the gut, the first time I laid eyes on a photo taken at the White House in 1965.

A dozen or so white men are all marching in a circle, carrying picket signs. They were homosexuals and they wanted equal rights. They didn’t want to seem too radical about it. So they had on suits to fit in and look “employable.”

And then there’s the Black woman. The only one in the photo. Her name, I would learn later, was Ernestine Eckstein.

With queer lives and culture under threat, Our Queerest Century highlights the contributions of LGBTQ+ people since the 1924 founding of the nation’s first gay rights organization.

Pre-order a copy of the series in print.

She too was a homosexual — well, a lesbian — and wanted equal rights. She carried a picket sign and had on a suit and white-framed sunglasses. She looked “employable.” But it was the height of the civil rights movement. She had to know her dark skin screamed radical. She was never going to fit in. Yet, around she went with those white men, her sign declaring: “Denial of Equality of Opportunity Is Immoral.”

Back then, I was fresh-ish out of the closet and had just started working as a columnist in Indianapolis. I wanted to write about my queer identity, but I quickly realized that, unlike race and gender, sexual orientation was not a protected class under state law.

I worked in a city with an ordinance that forbade such discrimination. But I was still a mere ZIP Code away from being fired for being queer, and it was an odd, infuriating and helpless feeling to be legally split into three. Besides, I’d heard horror stories about rogue employers. And I needed my job.

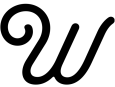

A June 1966 issue of the Ladder: A Lesbian Review, which provides one of the few known photographs of Ernestine Eckstein.

(Tracie Van Auken/For The Times)

I shrank into cowardice.

Meanwhile, there was Eckstein, who seemed fearless. A lifelong activist, she started as a student with the NAACP and the Congress for Racial Equality, or CORE. She moved to New York and became chapter vice president of one of the era’s top gay rights organizations, the Daughters of Bilitis. Later, she got heavy into feminism and moved to California, joining San Francisco’s Black Women Organized for Action. She died in 1992 in the East Bay city of San Pablo.

If you’ve never heard of Eckstein, don’t worry. Most people haven’t. I’m convinced the only reason I did is that I lived in Indiana and she was a native Hoosier — born Ernestine Eppenger in South Bend, the same city from which Pete Buttigieg rose from mayor to the nation’s first out gay Cabinet member.

Eckstein once described rights movements as needing “courageous martyrs” — a term I’d apply to her. More than ever, we need to understand and uplift such people.

Any movement needs a certain number of courageous martyrs. There’s no getting around it… You have to come out and be strong enough to accept whatever consequences come.

— Ernestine Eckstein

This country has long sliced and diced its citizens’ intersectional identities through a patchwork of legal protections at the local, state and federal levels. But what we’re seeing lately, with Republican governors, legislatures and judges proudly obstructing the rights of some for the perceived benefit of others, is a new and more dangerous level of legalized inequity, dehumanization and cruelty.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signs the Parental Rights in Education bill, also known as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, at Classical Preparatory School in Shady Hills, Fla.

(Douglas R. Clifford/Associated Press)

Republican-led states have introduced a wave of anti-LGBTQ+ bills, banning gender-affirming healthcare and forcing teachers to out their students. And that’s on top of the ongoing political attacks on women’s bodily autonomy and attempts to devalue diversity and whitewash Black history.

People who exist not only at the nexus of multiple identities, but of multiple movements for liberation will be the ones to show us a way out of this darkness. Even if most Americans don’t realize it, they’ve always been the ones driving us forward toward the light.

They recognize oppression first and are victimized by it first. They treat the struggle for equity and equality as an urgent necessity, not as a luxury to be reached one day — even when that means fighting for it while facing discrimination from one’s own communities. Their motives are selfish and selfless.

As Audre Lorde wrote: “It is the members of oppressed, objectified groups who are expected to stretch out and bridge the gap between the actualities of our lives and the consciousness of our oppressor. For in order to survive, those of us for whom oppression is as american as apple pie have always had to be watchers.”

Eckstein embodied intersectionality before it was even a word, publicly demanding to be treated as a whole human being worthy of equality under the law.

At age 33, I wondered what it would take for me to do the same.

I peeled the headphones off my head, thinking about the words I had just heard.

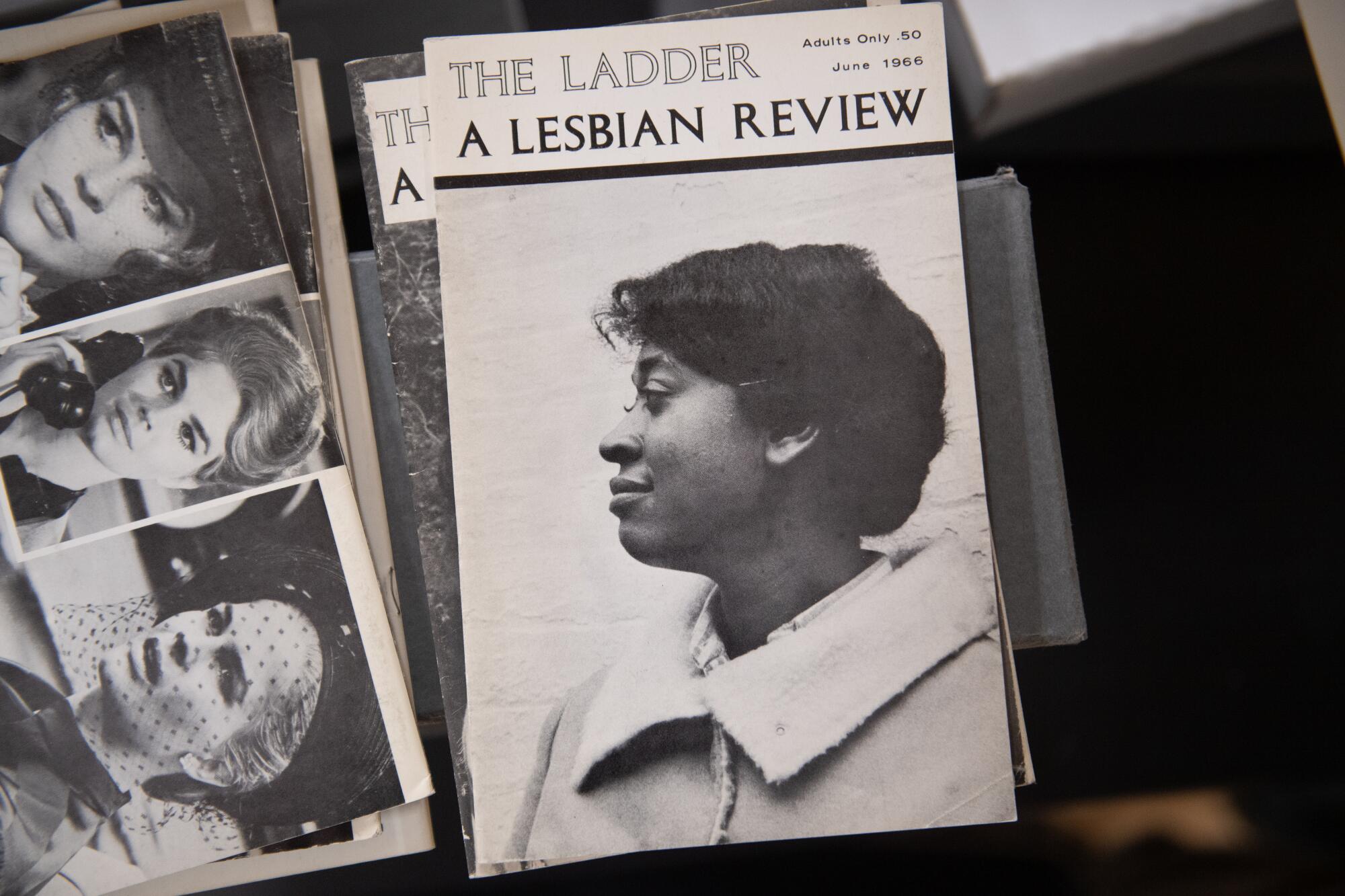

It was January, and I was sitting in front of a computer at the William Way LGBT Community Center, nestled in Philadelphia’s historic gayborhood. Years ago, the center’s John J. Wilcox Jr. Archives was given an audio recording of the only substantive interview that Eckstein ever gave. I wanted to put a voice to a photo. And what a voice!

Columnist Erika D. Smith listens to audio of an interview between Ernestine Eckstein and two other leaders of the Daughters of Bilitis, a lesbian civil rights group. The interview cassette tapes and digital copies are housed at the William Way LGBT Community Center in Philadelphia.

(Tracie Van Auken/For The Times)

Recorded in the mid-1960s, a young Eckstein shrewdly answers a barrage of questions from lesbian power couple Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen about what the nascent gay rights movement — then known as the homophile movement — should learn from the civil rights movement.

“They were treating her like she was under a microscope,” said Marcia Gallo, an author and historian of lesbian activism. “Like, ‘Who is this person?’ ”

This was the shame- and fear-filled era when most Americans believed queer people needed to be cured. Led by the Mattachine Society, founded in L.A. in 1950, and Daughters of Bilitis, founded in San Francisco in 1955, most queer activists — if they even considered themselves activists — were white.

Harry Hay, left, one of the founders of the gay rights movement, with his partner John Burnside in San Francisco in 2002. Hay devoted his life to progressive politics and in 1950 helped found the Mattachine Society.

(Ben Margot/Associated Press)

“They were really about trying to get people to not hate themselves,” Gallo told me, “and not buy into all this psycho sickness around sexuality that was happening [and] providing safe spaces for people to come together.”

Eckstein was different, though, battle-tested by the fight for civil rights. She advocated for protesting and building political power through then-unheard-of coalitions with gay men and trans people. She wanted to force the courts to take up more cases to challenge the discriminatory status quo.

“I think of her as a prophet of the movement,” said Eric Marcus, an author, historian and host of the “Making Gay History” podcast. “What she spoke about was foundational.”

Even more important than what Eckstein said was what she did. She led by example, exuding self-worth and self-love — traits emphasized by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and other civil rights leaders, and borne of the way Black people have always dealt with dehumanizing oppression without losing our dignity.

Eckstein wanted to be recognized as equal under the law because she wanted rights. But she didn’t need government to validate her existence as a Black person, a woman or a lesbian. As she told Gittings and Lahusen, in what was surely a radical statement at the time: “I’ve known heterosexual love, and comparing the two, I find homosexual love preferable.”

This refusal to give into shame speaks to just how much Black activists influenced the attitudes, tactics and policy priorities of early queer activists, altering the trajectory of their work.

Marc Stein, a professor of LGBTQ+ history at San Francisco State University, told me, “It wasn’t just a taking or an appropriation, but a new application of ideas and strategies carried from one movement to the next in the very bodies of people.”

In addition to Eckstein, there were trailblazers such as Pauli Murray, Bayard Rustin, Cleo Bonner, Pat “Dubby” Walker and James Baldwin, to name a few. But Eckstein was a singular figure, Stein said, because she was so unafraid.

Columnist Erika D. Smith holds a pamphlet showing Ernestine Eckstein at a Washington, D.C., march in 1965.

(Tracie Van Auken / For The Times)

That photo of her outside the White House was taken during an offshoot of Philadelphia’s controversial Annual Reminder protests, held to inform Americans that queer people lacked civil rights protections. The idea came from the late Frank Kameny, an Eckstein ally and astronomer-turned-activist who refused to accept being fired from the Army Map Service for being gay.

Kameny sued for workplace discrimination, the first case based on sexual orientation to land before the U.S. Supreme Court. He lost but looked to the civil rights movement for how to keep fighting. He adopted the motto “Gay is good” — a spin on “Black is beautiful” — and took the advice of Black activists such as Cecil Williams of San Francisco’s Glide Memorial Church, who urged queer people to have “pride.”

Mostly, Kameny raged about how a supposed cure for homosexuality was insulting and irrelevant to calls for equal rights.

“I do not see the NAACP and CORE worrying about which chromosome and gene produced a Black skin, or about the possibility of bleaching the Negro,” he said in 1964.

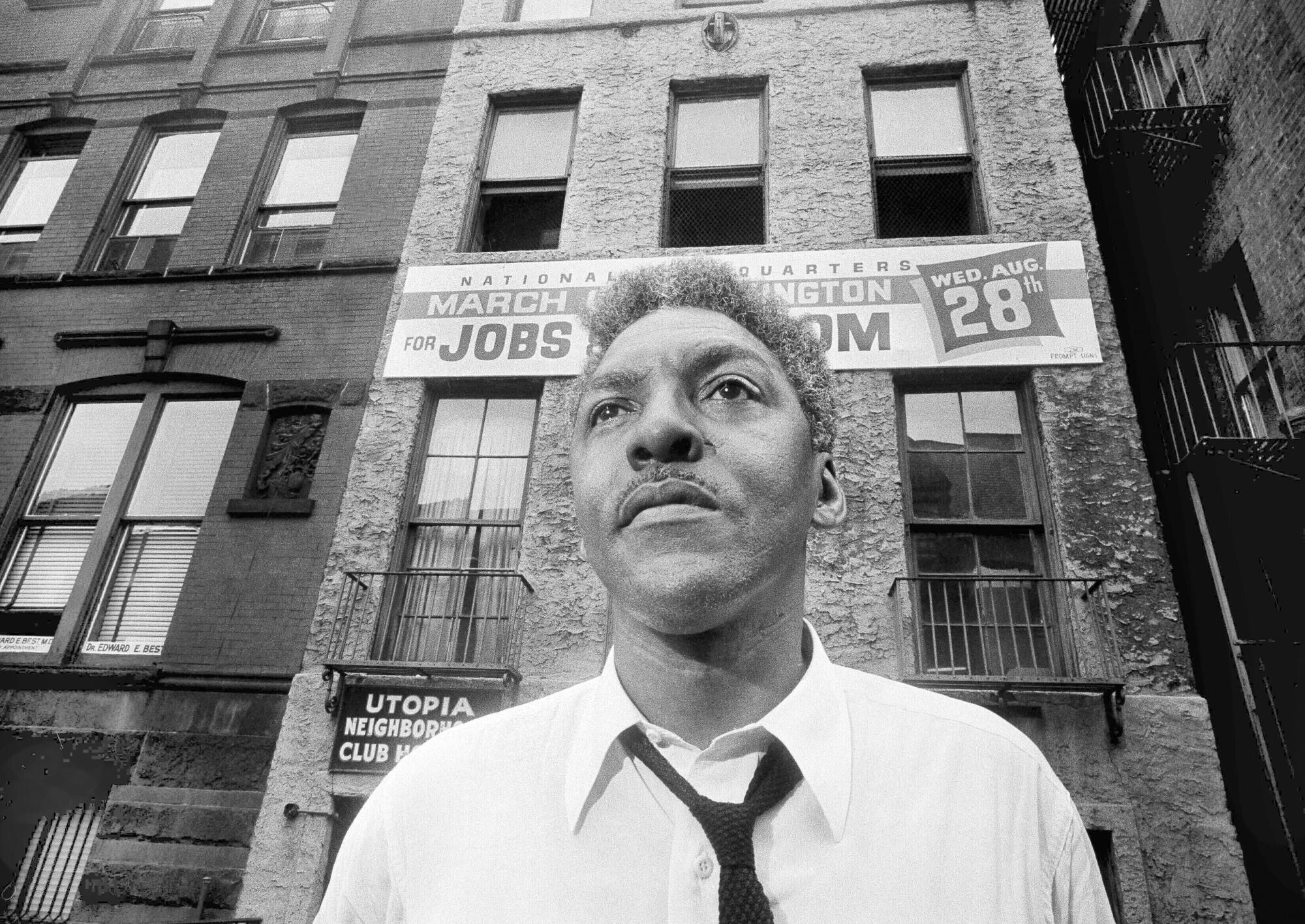

Until last year, most Americans probably hadn’t heard of Bayard Rustin. Then, the production company founded by Barack and Michelle Obama released a movie about the queer Black civil rights activist who co-founded CORE and organized the March on Washington.

Bayard Rustin, leader of the March on Washington, in New York in August 1963.

(Eddie Adams / Associated Press)

“This is someone who was courageous enough to be who he was despite the fact that he was most certainly going to be ostracized, fired from jobs, pushed aside,” the former president said at a screening in Washington. “And that’s what happened.”

Without Rustin, there would’ve been no March on Washington in 1963 and no Civil Rights Act of 1964. Without the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many of the rights we count on in 2024 wouldn’t exist. But Rustin was nearly erased from history because he refused to hide his queer identity.

In a 1986 interview, he explained why.

Rustin said he had been headed toward the back of a bus in the South in the 1940s, when a white child tried to grab his tie. He said he heard the mother admonish, “Don’t touch a n—,” and something inside him shifted.

“If I go and sit quietly in the back of that bus now, that child who was so innocent of race relations that it was going to play with me, will have seen so many Blacks go in the back and sit down quietly that it’s going to end up saying, ‘They like it back there,’ ” Rustin recounted. “… I owe it to that child that it should be educated to know that Blacks do not want to sit in the back.”

Not long after that, something else shifted. Rustin realized that “it was an absolute necessity for me to declare homosexuality,” because if he didn’t, he was “aiding and abetting” prejudice. “The only way I could be a free whole person was to face the s—.”

Society likes to put people in boxes. It’s neater and easier that way because intersectionality is messy. But the people who work the hardest to make this country better have never truly confined themselves like that.

Take Phill Wilson.

As a Black gay man who moved to Los Angeles in 1982, he saw the disjointed response to HIV/AIDS. Black people were dismissing it as a “white gay disease,” even though we were the ones disproportionately getting sick. And the white gay people who were leading the public health response refused to address the unique needs of the Black people most at risk.

“In both communities, it was kind of, ‘That’s not our problem,’ ” Wilson told me. Infections and deaths continued to rise.

Phill Wilson, president and CEO of the Black AIDS Institute, during a September 2012 event in Los Angeles.

(Arnold Turner/Associated Press)

In response, he founded the Black AIDS Institute, confronting the virus and disease through alliances with Black leaders and institutions. He faced homophobia from Black people and racism from white queer people. But without embracing his identity, he couldn’t have built a nonprofit that normalized culturally competent approaches to fight infectious diseases — approaches the country would fall back on during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rather than the hindrance some saw for Rustin, intersectionality proved to be a strength for Wilson.

“I never left any of myself outside the room,” he said. “In Black communities, I was able to personify that Black people could be gay and Black people could also live with HIV. And in white gay spaces, I could personify that not all gay people are white.”

This also allowed Wilson to leverage the influence of King’s widow, Coretta Scott King. “She was very, very easy to convince to get involved [with the Black AIDS Institute], and I think it was because of her relationship with Bayard,” he said.

Rustin died in 1987, still an activist at age 75 and outspoken about HIV/AIDS.

In 2020, a few years after Obama awarded him a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom, Gov. Gavin Newsom granted Rustin a posthumous pardon for a 1953 arrest in Pasadena for being in a car with men and having sex — a case that had been life-altering for Rustin. Used by Black leaders as a tool of humiliation, it’s why he quit the powerful Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

King eventually stood up for Rustin, resolving a rift over homophobia in their friendship, but not in the civil rights movement. That wouldn’t come until decades later.

I didn’t grow up going to church, but I always understood its power as an institution. For generations, Black people have gathered at houses of worship to plot ways to fight oppression, usually looking to pastors to lead the way.

But that changed in 2013 after a Florida jury acquitted a neighborhood watch captain in the killing of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black teenager. Distraught, a Black queer woman from L.A. named Patrisse Cullors logged onto Facebook and typed #BlackLivesMatter. A new call-to-action was born.

“The Black church had to really contend with us and what it meant for the leadership of this iteration of the civil rights movement to so loudly identify as queer,” Cullors told me.

Many of the young activists who took up the banner of Black Lives Matter had been “demonized” by the church because of their sexual orientation and gender identity. They saw Rustin as a cautionary tale. Someone who, Cullors said, “sacrificed so much of himself because he was asked not to be himself,” and they weren’t willing to do that.

Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors speaks at a news conference at Los Angeles City Hall in January 2023.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Nor were they willing to ask politely for police to stop killing Black people. They blocked freeways and normalized sharing hashtagged videos on social media to whip up public outrage. Indeed, without Black Lives Matter, we wouldn’t have had a racial reckoning after Minneapolis police killed George Floyd in 2020, which led to widespread understanding of systemic racism and intersectionality.

They also drove home the fact that Black transgender women are most at risk for discrimination and violence — including by law enforcement.

“What the early days of BLM did was say, ‘Guess what, Black straight people? Black queer and trans people exist. We are part of your community, and we have to actually fight for all of us,’ ” Cullors said.

That’s easier said than done, though.

Ebony Harper, founder of the Sacramento-based advocacy group California TRANScends, has spent years fighting to pass legislation to help transgender Californians. But some of the toughest fights she’s had weren’t in the capitol, but outside it as an activist.

In 2018, after Sacramento police shot an unarmed Black man named Stephon Clark, Harper joined a series of Black Lives Matter protests. Growing up in Watts and experiencing the aftermath of the beating of Rodney King, she felt at home in the crowd, angry about the ongoing oppression of Black people. Then she met activists who questioned whether she was a “real woman.” It reminded her of a childhood in which her mother regularly pitted her Blackness against her queerness.

But not participating in a movement for liberation? That was never an option.

“I’m for my people, even though I’ve been rejected,” Harper explained. “I understand that our struggles are connected. To me, it’s about what’s right and what’s wrong.”

About a year before I first saw that photo of Eckstein at the White House, my friend Anthony — Black, from West Virginia and oh-so-very gay — told me something I’ll never forget: “You’ll know you’re done coming out when you’re as comfortable with your gayness as your Blackness.”

Columnist Erika D. Smith stands outside of the William Way Center in Philadelphia.

(Tracie Van Auken / For The Times)

At age 46, I realize that, somewhere along the way, this happened for me. First, I learned to accept myself. That gave me the courage to be visible. And that, in turn, alleviated the fear of publicly demanding equality.

Living in California, where I have lots of rights as a queer person, has certainly helped this evolution. But to live in California also is to live in a complacent bubble of liberalism. Case in point: While I was still working at the Los Angeles Times and the U.S. Supreme Court finally ruled that it was illegal — under the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — to fire people over sexual orientation or gender identity, I wasn’t even impressed.

Too much of America is not like California. Now, more than ever, we need to listen to courageous intersectional martyrs. Like Eckstein.