José Andrés spends much of his time contemplating the unifying nature of food, both in and out of the world’s most dangerous conflict and disaster zones.

Days before an Israeli airstrike killed seven members of his aid organization working to feed Palestinians in Gaza, Andrés spoke to The Times about his recently published cookbook “Zaytinya.” Andrés is scheduled to speak at the 2024 Los Angeles Festival of Books, on April 21. The April 1 Gaza bombing that killed his fellow aid workers thrust Andrés further into the global limelight, and spurred international calls for accountability from the Israel Defense Forces and for an independent investigation.

In addition to owning dozens of restaurants spread around the globe, the Spanish chef has become synonymous with food aid through his organization World Central Kitchen, which dispatches chefs and other volunteers to feed people in the wake of wars and natural disasters.

“I wish that the world was run by people that cook and feed, because this is something that brings everybody together,” Andrés said on a phone call three days before the attack.

The Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean regions have always been particularly dear to him. The sights, scents and tastes have proved somewhat of a compass for the chef, especially over the last 22 years.

At his Washington, D.C., restaurant Zaytinya, a haute but tradition-minded exploration of Lebanon, Turkey and Greece, he pursues the culinary ties found across these cultures and the birthplace of some of the world’s most ancient and influential cuisines. He hopes his new Zaytinya cookbook will further share the beauty of the region.

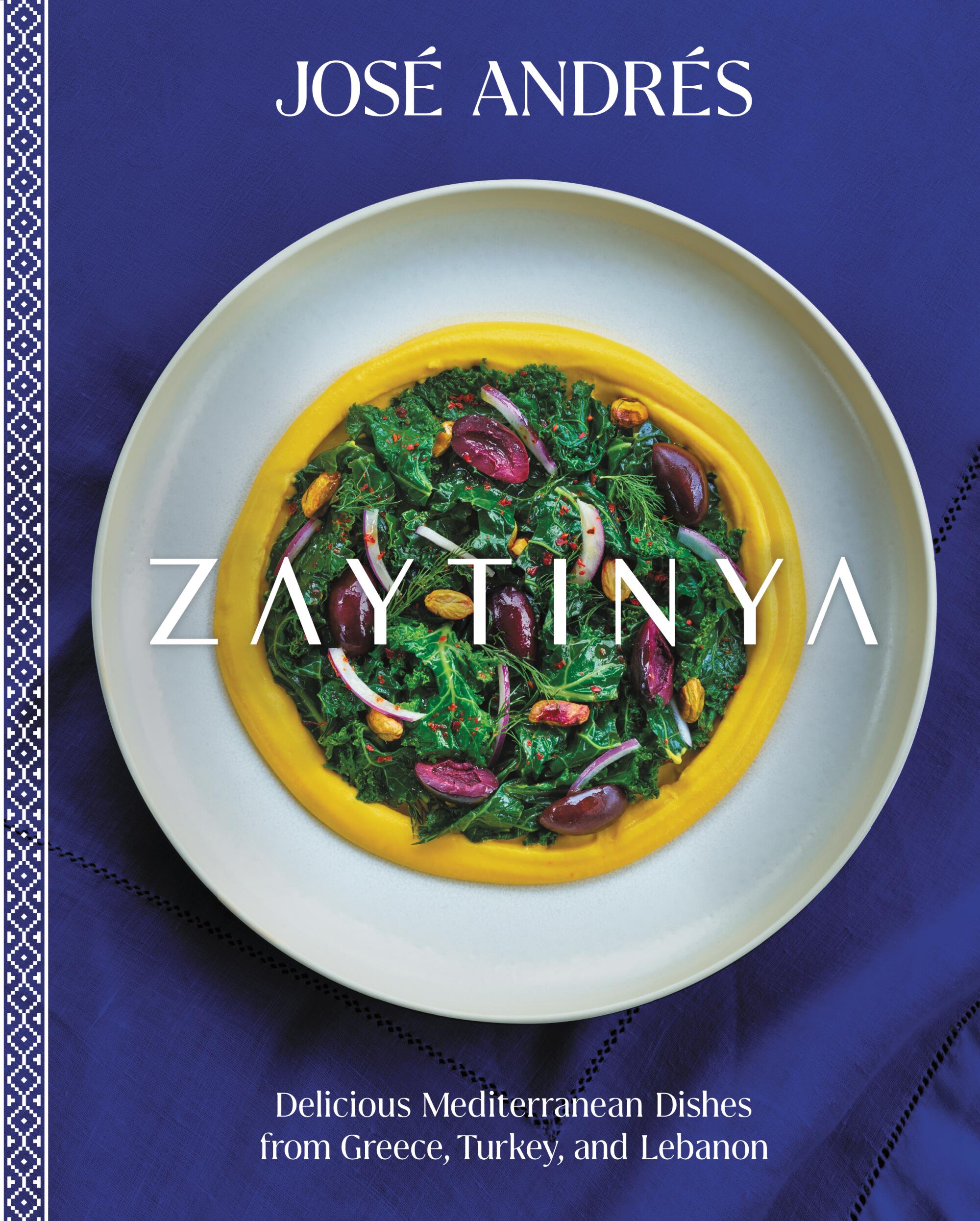

The “Zaytinya” cookbook by José Andrés.

(Ecco)

Andrés and his wife, Patricia, ducked into cobblestone alleyways and bazaars, home kitchens and high-end restaurants across the Levant, consulting chefs and merchants and other authorities to bring the restaurant to life.

He debuted Zaytinya in 2002, the kind of place where Lebanese-inspired butternut hummus, Turkish braised lamb shank and Santorini-style whole fish sit side by side — ideally on a table shared with a bevy of friends and family. Eventually he would expand this restaurant to Florida and New York, and soon, to Palo Alto and Las Vegas (Los Angeles is not slated to receive Zaytinya, though an outpost of the chef’s steakhouse, Bazaar Meat, is expected to open downtown this fall, near sibling restaurants San Laurel and Agua Viva).

At Zaytinya the focus is on dishes’ shared connections. And within the cookbook, items enjoyed across the regions are titled in multiple languages.

“The meaning to me of culture is not something exclusive, but something inclusive,” he said. “It’s not something that only belongs to you, but belongs to everybody. Culture to me is the perfect synonym for longer tables, for sharing. Culture is not what I know but what I’m sharing with others, and what others are sharing with me. That’s why I never understood cultural appropriation in the way of food.”

Since opening Zaytinya he’s witnessed these cuisines and so many others extending to all corners of the globe, especially with the internet, which has made sharing those cultural ties to food infinitely accessible.

Butternut hommus, featured in “Zaytinya,” garnished with pumpkin seeds and pomegranate molasses.

(Photo by Andrea D’Agosto, Food Styling by Caroline Hwang, and Prop Styling by Nia Lee / For The Times)

Ingredients ubiquitous across the Middle East and the Mediterranean, such as za’atar, can now be found not only in specialty restaurants like Lebanese Taverna or Zaytinya, but on big-box grocery shelves across America. He welcomes the discourse over who invented what, but focusing only on this is, in a way, missing the forest for the trees.

“If we move borders, there is people,” he said. “If we take no borders, no frontier, there is people. Everybody loves hummus and everybody loves falafel. There’s certain things that go beyond borders and frontiers, and there are dishes that belong to the people.”

“You say tzatziki, I say cacık,” he added. He’s encountered it with his own culture, too, gladly diving into the contentious debate over whether Spanish coca, or flatbread, inspired Italy’s pizza on an episode of food travel show “José Andres & Family in Spain.”

The Zaytinya cookbook arrived six months on the heels of “The World Central Kitchen Cookbook,” a sprawling and colorful collection of global recipes from Andrés and participating chefs, and one that fundraises for the organization.

“People were asking for the recipes because it’s amazing the love that people put in recipes in emergencies,” he said. “It’s amazing the diversity of meals we’ve done throughout our history.”

In many ways, the cookbooks are wildly different: Zaytinya, he said, is about feeding the few while World Central Kitchen’s tome is about feeding the many. But in some ways the ideas were similar in translation and global nature: With Zaytinya, the recipes came from the restaurant and its connections to the outside world, and in the World Central Kitchen cookbook, the world serves as the restaurant.

Though the chef said he tries to keep his restaurant empire separate from his humanitarian organization, the ethos sometimes overlaps. Zaytinya doubled as a hub for nourishment and aid in March 2020, when Andrés flipped the restaurant and his others into community kitchens during the pandemic, offering budget-friendly dishes, pay-it-forward options and outright-free meals for those in need.

Over 800 people lined up to receive food in one of eight locations around Kherson, Ukraine, that was liberated from the Russians military in November 2022. José Andrés’ World Food Kitchen was among the first aid groups to push into the just-liberated city, bringing in truckloads of food and supplies.”The hug you get,” said Andrés, “is worth a billion pounds of food.” WFK is giving away 6,000 food packages per day in Kherson, Ukraine alone.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

“Water and food need to be named and seen as a universal human right,” Andrés said. “Every human on Earth, every child, should have access to food and water, no matter what. I don’t know anybody that disagrees with this statement, but then we don’t make it happen. And we’re leaving people hungry.”

He continued: “Obviously that’s happening right now in Gaza, but that’s happening in many places around the world. We have the bounty of the goodness of the Earth, but still we are not able to solve hunger even in rich countries.”

Andrés knows that one restaurant, one cookbook, one nonprofit cannot solve this. Still he feels he has to try, and that the accumulation of efforts could make a difference.

They also serve another purpose: to preserve and share culture — at least as best they can.

“Restaurants are important because they ground an ethnic cooking in a neighborhood in the city, but there really is a lot happening in the home too,” he said.

According to Andrés and Greek food writer and consultant Aglaia Kremezi, who penned the book’s foreword, Greek, Turkish and Lebanese cuisine can all be particularly hard to replicate in a restaurant setting due to the soulful, rustic nature of their home cooking.

Chef José Andrés visits Athens Market in his new “Zaytinya” cookbook, which shares recipes from his Greek, Lebanese and Turkish restaurant of the same name.

(Thomas Schauer / Ecco / HarperCollins Publishing)

André tasted kolokithokeftedes, or Greek zucchini fritters, in a little restaurant not far from the airport in Santorini. He’d gotten lost, but a dining sign affixed to what looked like a small house caught his eye. Andrés ordered the fritters and found them to be amazing; he attained the recipe and added them to the menu at Zaytinya but, he said, has never been able to re-create them exactly as they were in that homey restaurant in Santorini. In his own home he’s gotten closer, but in the restaurant they feel further from their origin.

For all his spherification and whimsy and molecular gastronomy at his restaurants like Minibar and the Bazaar, much of his cuisine at restaurants such as Zaytinya and Jaleo are served true to their roots. “In my way of doing those ethnic cookings,” he said, “I always put the responsibility on myself to be as truthful as I could from the tradition.”

Those kolokithokeftedes are included in the Zaytinya cookbook with so many other homestyle, comforting recipes from the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East — maybe they’re most true, most replicable, cooked at home for your loved ones too.

José Andrés is slated to speak at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books on Sunday, April 21, at 12:30 p.m. at Bovard Auditorium. Tickets are for sale at events.latimes.com/festivalofbooks.

The Recipes

Time15 minutes

YieldsServes 4

Time2 hours, 5 minutes

YieldsServes 6

Time1 hour, 15 minutes

YieldsMakes about 3½ cups