On Oct. 7, Hamas terrorists invaded southern Israel, murdered approximately 1,200 people and abducted more than 240 others. One of those kidnapped was my 35-year-old son, Sagui, who lived on Nir Oz, the kibbutz I’ve called home for most of my adult life and which was destroyed during the attack. Sagui is among the 120 hostages still held by Hamas.

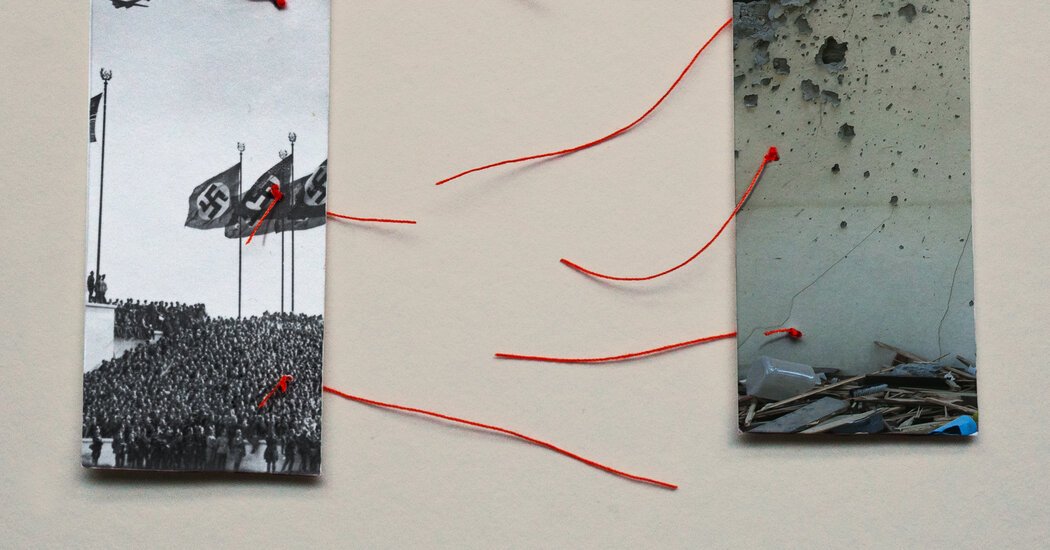

That horrific day and the devastation of Gaza caused by Israel’s military response have led to countless references to the Holocaust and related terms: genocide, Nazis, pogroms. Some of Israel’s opponents have loosely and irresponsibly accused Israel of genocide against the Palestinians. My own government has also invoked those terms, mainly to convince Israelis of the magnitude of the threat they face from Hamas.

As the son of a father who survived the Holocaust and a mother who fled Nazi Germany, I find our government’s use of such references to the Nazi genocide to be deeply offensive. As the father of a hostage, I find the use of such language excruciating. And as a professor of history, I am appalled at the inaccuracy of such statements and frightened by their implications for Israeli society.

There is one truth to our leaders’ invoking of the Holocaust: Oct. 7 was indeed the deadliest single day for world Jewry since the Holocaust. The comparison ends there.

By invoking collective memories of the Holocaust, Israeli government ministers and other leaders are effectively absolving themselves of the horrors of that “Black Saturday” — in effect, shirking their own accountability for the massacre and their sacred responsibility to return all the hostages alive.

In fairness to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s current ministers, earlier governments have also invoked Holocaust images to mobilize the country. The practice dates back to David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s founding prime minister, and includes Prime Minister Menachem Begin, who compared the Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat to Hitler in 1982. Since Oct. 7, however, the frequency and intensity of these statements seem far greater.

This month, Mayor Moshe Lion of Jerusalem — addressing an audience at the gala before a conference in New York — spoke of attacks on Jews on campuses and in the streets “like we have not seen since 1930s Germany.” Ofir Akunis, Israel’s consul general in New York, said at the conference that Hamas’s goal was to commit “genocide” of Israelis, saying that the term referred “to the Holocaust itself and nothing less.”

These are only the latest in a drumbeat of such statements.

“The horrific stories we hear from the survivors of the Hamas attack remind me of the stories my mother told us about the Holocaust,” Foreign Minister Israel Katz said to the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations in February. In November, Finance Minister Bezalal Smotrich said the West Bank had a population of “two million Nazis.”

Mr. Netanyahu himself has recently taken a different tack. He said in a speech on May 5 observing Holocaust Remembrance Day that the Oct. 7 attack was unlike the Holocaust because Hamas could not execute a full-scale massacre, implying that the Israel Defense Forces stopped an even larger attack. In fact, heroic civilian emergency workers and uncoordinated actions by small I.D.F. teams — and even individual soldiers — blunted the attacks with little or no guidance from their commanders.

My parents, who died years ago, would have been devastated by Israel’s failure to defend its citizens on Oct. 7, a betrayal of the fundamental reason for the country’s establishment in 1948. I believe they would have struggled to cope with the physical destruction of our kibbutz, where more than a quarter of all residents were murdered or kidnapped that day. Moreover, the pain they would have felt over the kidnapping of their beloved grandson Sagui would surely have been unimaginable.

Oblivious or cynical Israeli officials suggest that antisemitic statements and anti-Israel protests around the world recall Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Yet the protesters have almost no support from powerful politicians, industrialists and financiers, the kind of people who bankrolled and facilitated the rise of National Socialism in Germany. Nor do they have a leader, a party structure or a common ideology. They are not protesting within a failed state — like Weimar Germany — which was too weak to deal with violent demonstrators. On the contrary, one could say that some of the authorities are overreacting to the campus protests by calling in the police and bringing harsh disciplinary measures.

Instead of seriously examining the causes of pro-Palestinian and anti-Israel protests, these cynical officials are short-circuiting any attempt on Israel’s part to engage with the root causes of this anger: the large-scale civilian casualties in Gaza that have sapped our government’s ability to maintain any moral high ground in this conflict.

The analogy comparing the Oct. 7 attack to a pogrom, too, is false. Historians have shown that pogroms in 19th- and 20th-century Eastern Europe were almost always cases of mob violence, which at times local officials or the police encouraged. By contrast, the butchery of Oct. 7 was directed by Hamas, an organized group that planned it meticulously. References to mob violence only obscure its responsibility.

Invoking the mass extermination pursued by the Nazi regime is equally pernicious. In 1939 there was no sovereign Jewish state with an army. Now there is an Israeli army, which has protected the Jewish people from its neighbors since 1948.

We must come to grips with this simple truth: Israel’s government and military establishment have become arrogant and self-assured. Had they not fallen victim to a complete lack of imagination and an unwillingness to take seriously contrarian analyses from within their ranks, as has been widely reported, Hamas’s attack may very likely have never happened and certainly would not have been so deadly.

Cynically invoking the Holocaust and pogroms for political purposes is neither historically accurate nor necessary to demonstrate the inhumanity of Hamas toward Israelis and the people of Gaza.

On the contrary, it insults the memory of the countless victims of antisemitism in the past, including my parents. The Israel-Hamas war is proof that weaponizing language on all sides only prolongs hatred and conflict, in great part by allowing the participants to deflect attention from fundamental issues, including the Israeli government’s failure to bring all of our hostages home.

The true legacy of the Holocaust for Israelis should be a story of redemption and reawakening, one in which our people were not stamped out. The legacy should not be one of eternal victimhood at the hands of evil-minded forces, as our leaders constantly suggest.

There is nothing of greater value in the Zionist project than the continuity of the Jewish people, in a Jewish land, aware of, but not enslaved by, collective memories of our past.

Jonathan Dekel-Chen is a professor of history at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Source photographs by Library of Congress and Amir Levy, via Getty Images.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, WhatsApp, X and Threads.