The forces behind the relentless land movement plaguing Rancho Palos Verdes appear to be more complicated, and possibly more widespread, than originally thought — forcing the city to once again rethink how it can limit some of the mounting damage.

Officials confirmed a very deep and active landslide plane — previously considered dormant — during exploratory drilling this summer, a discovery that has upended emergency efforts aimed at stabilizing the Portuguese Bend area.

“This is an unprecedented new scenario for the city, which means we have to change our strategy,” Ramzi Awwad, Rancho Palos Verdes’ public works director, said during a City Council meeting last week.

Again.

Officials also characterized the situation as unprecedented this winter, when, after back-to-back years of extremely wet rain seasons, land movement accelerated and expanded in ways never before seen: splitting homes’ walls, ruining roadways and repeatedly bursting underground utility lines.

The alarming situation prompted the city to shelve a long-term stabilization plan and pursue emergency efforts to slow the land movement.

But the recent discovery of this active, deeper slip plane, which sits at roughly twice the depth of the previously tracked landslides, further muddles any possible solution to the growing disaster.

Geologists believe the deeper activity is the ancient Altamira landslide complex, for which movement has never before been recorded, Awwad said.

“The shallower slide does have fast movement, but the deeper slide is moving much faster,” Awwad said. “The priority becomes that deeper slip plane.”

The discovery only exacerbates the sense of urgency. In the last few weeks, Southern California Gas Co. shut off service to 135 homes in the landslide area, citing safety concerns from the worsening land movement. Soon after, Southern California Edison warned electricity could follow “if conditions warrant.”

Many Rancho Palos Verdes residents are facing existential threats to their homes — cracked foundations, leaking roofs, shifting floors — and the Los Angeles County Fire Department, which serves the Palos Verdes Peninsula, has warned it could take first responders more than six minutes to access some homes due to challenging road conditions.

This week, a group of residents filed a lawsuit in state court alleging local officials — including the homeowners’ association, the area’s water provider, the city, the county and landslide abatement district — failed to properly act, leading to an oversaturation of nearby hillsides that triggered the recent landslide movement.

“Our city is doing everything, but the problem is, the problem is bigger than our city,” said Mayor John Cruikshank.

City officials last week voted to move ahead with a pilot plan to drill vertical wells into the deeper landslide, with the aim of pumping out groundwater — known to be the impetus for the land movement — while continuing to study the extent and characteristics of the deeper slip plane.

For the record:

9:07 a.m. Aug. 26, 2024An earlier version of this story said that removing groundwater reduces friction. Removing groundwater does not reduce friction — it increases it.

Much about this deeper, ancient landslide remains unknown, but it’s clear it at one point encompassed a much larger area, meaning it could potentially warp even more land, infrastructure and homes.

Land movement exacerbated by storms caused large cracks in the pavement and damaged nearby homes on Dauntless Drive in Rancho Palos Verdes.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

“The boring program, thus far, has confirmed there is a much deeper landslide … probably the ancient Altamira landslide,” said Mike Phipps, the city’s contracted geologist. “What we don’t know is whether that deeper landslide extends under the entire complex.”

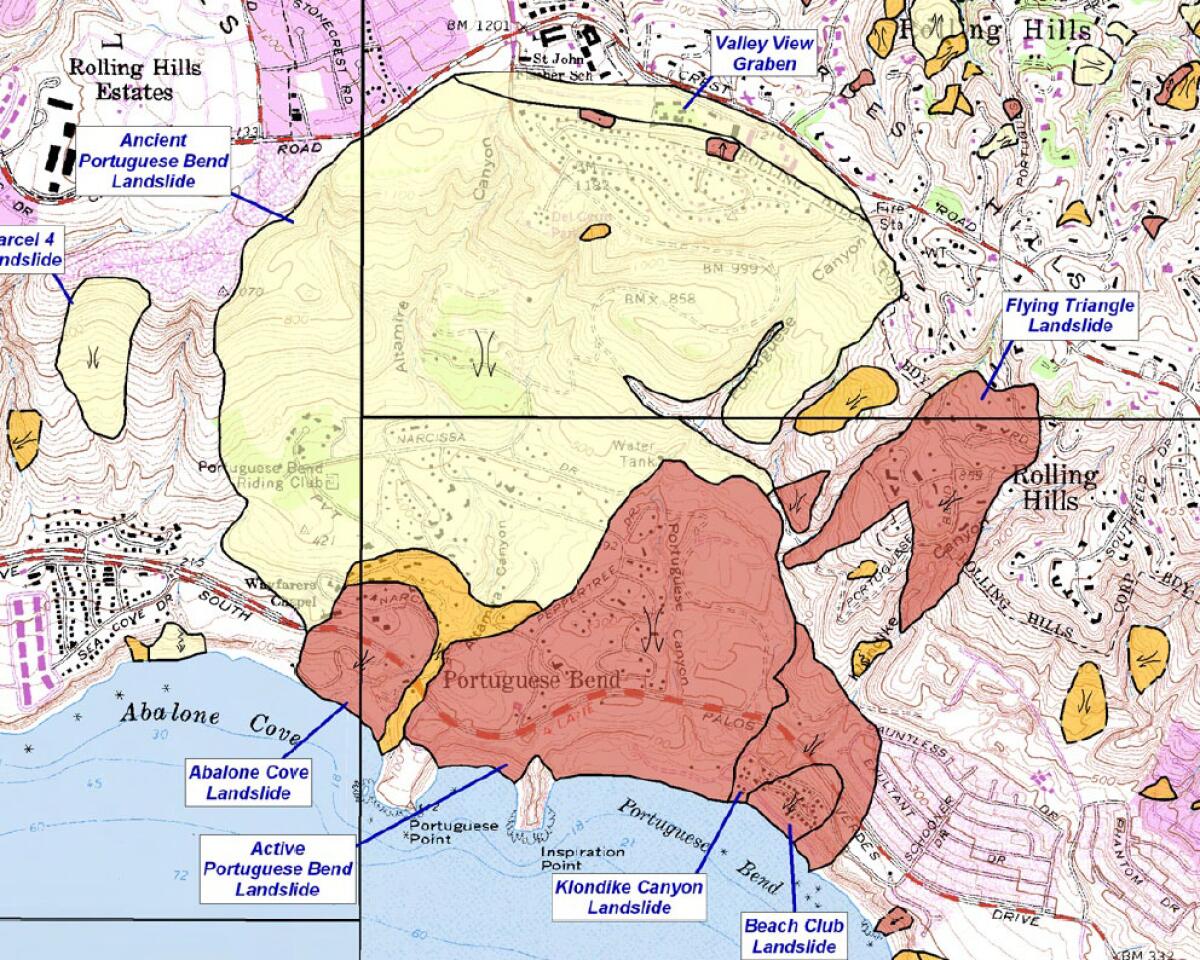

Historical maps of the ancient landslide complex, including one from the California Geological Survey, documented the slide’s boundary to be well north of the Portuguese Bend Reserve, almost reaching Crest Road — which would include some neighborhoods off Oceanaire Drive and Valley View Road.

Other mapping does not include those areas, however, and Phipps noted that recent movement, or other factors, could have shifted the ancient perimeter.

His team recently installed additional monitoring sites in the neighborhoods south of Crest Road, hoping to better understand the scope of current and potential movement.

There’s also been some new land movement northeast of the landslide complex along Cinchring and Quail Ridge roads in Rolling Hills, an area that has never been included as part of any mapped landslide area.

“It could be related, but it could be a separate landslide,” Phipps said. “We really don’t know.”

He encouraged collaboration between the cities of Rolling Hills and Rancho Palos Verdes to figure out what’s happening, and whether the movement is related.

“In the future, this could be a public safety issue for Rolling Hills,” Phipps said.

Rolling Hills City Manager Karina Bañales said city officials have been “engaged in ongoing conversations” about the “regional land movement,” but noted that the areas probably affected are on private property.

Boring tests that uncovered the deeper geologic formation have so far been completed along only one edge of the Portuguese Bend landslide, which is one of four smaller slides in the area — along with Abalone Cove, Klondike Canyon and Beach Club — that probably sit atop the Altamira Complex, according to the latest report from city officials.

The failure surface of the Portuguese Bend landslide, previously the largest of the group, was recorded around 80 to 180 feet below ground level. The deeper slip plane associated with the ancient Altamira slide was measured around 245 to 345 feet below ground, the report said.

The California Geological Survey’s map of the ancient Portuguese Bend, or Altamira landslide, which was previously considered dormant, shows the most expansive boundary of the landslide area in yellow, with recently active slides in red.

(California Geological Survey)

The prevailing thought has been to respond to each of these smaller slides separately, but Awwad and Phipps said a more unified approach is now warranted, given the deeper, faster and more widespread Altamira slip plane that spans the other slides.

Despite the onslaught of concerning news, Phipps said there is a bright spot. For the first time in months, recent measurements from across the landslide area — from July 1 to Aug. 1 — showed the overall rate of land movement had decelerated, by about 1%.

“The general rate of land movement has actually leveled off,” Phipps said. “This doesn’t mean the movement has stopped. … The landslide is still moving three-and-a-half to four-and-a-half feet per month — but it’s not accelerating anymore.”

Movement is still slightly accelerating in some areas, but at much lower rates than previously reported. However, Phipps notes that the area is still shifting about 88 times faster than it was in October 2022, when he was measuring movement on the order of inches per year, not per week.

“Landslide movement continues to manifest at the ground surface in the form of scarps, fissures, grabens/sinkholes, tensional cracking, shear zones and thrust features,” the city’s latest report said. “Due to the continued movement of the landslide, the ground movement features have continued to enlarge, expand, widen, or grow depending on the type of feature and location.”

And that means the problem is still a long way from being solved.

Cruikshank appeared almost exasperated by the situation last week, questioning how anyone can ignore the growing crisis, noting that many people living in this area are seniors on fixed incomes. Earlier this month, the city requested — again — for the state to declare an emergency given the recent gas shutoffs, and Cruikshank even appealed for help from Elon Musk.

Officials said they’ve yet to get a response from either.

“We do need that help, but honestly I don’t know if I expect it anymore,” Cruikshank said at the City Council meeting. “Quit looking at us like as a rich community that doesn’t need help — we need help.”