Everyone loves Glastonbury. Those lucky enough to have been there know it’s the greatest party in the world. Those who have only seen the BBC’s lavish annual coverage know it as a true national institution. Its popularity means it can sell around 140,000 tickets, at £378.50 each, in minutes. It can charge vendors thousands and thousands for a pitch, as well as sell hospitality tickets for £780.

It also has the most pored-over lineup in the world. Its headliners are speculated on years in advance. If you wanted to know what the best live music was in a certain year, you’d have no better authority than looking at the festival’s lineup. It should be a great feeling, in short, to play Glastonbury. Yet, having talked to scores of people connected to Worthy Farm, it’s quite jaw-dropping to learn that pretty much every single act on the bill – from top to bottom – loses money from playing Glasto.

Let’s start at the Pyramid Stage. It’s common knowledge that Glastonbury pays its major headliners less than their typical fee. But it’s a calculated move: big online buzz and guaranteed live coverage on the BBC means that any shortfall can usually be recouped by increased streaming and tickets sold for future tours. One major act reportedly spent £80,000 of their own money on a Glastonbury show a few years ago, knowing they were getting prime BBC coverage. It quickly led to them selling out three major London dates, so their lack of a direct fee from Glastonbury didn’t impact them. Bands repeatedly stress in private that it’s essential to have a “TV plugger” in their Glastonbury team to guarantee that precious BBC exposure.

If they can’t afford a plugger, a sharp cliff-edge emerges. Put simply, not getting shown on the BBC can suddenly make Glastonbury hugely expensive. Singer-songwriter Nadine Shah went public about this last year, pulling out of the fest after she learnt she “wasn’t offered a televised stage”. “It’s too expensive a hit for me to take otherwise,” she claimed on X.

“Pay to play” is a phrase that a lot of acts and musicians use when describing the Glastonbury experience. Many major, name-recognisable acts are paid in the hundreds of pounds – absolutely not enough to cover the expense of their transport, crew and accommodation. Some take the hit for the love of the festival. Others do it, but have to schedule another gig (for a much better fee) on the same weekend to offset the loss. It’s the same for big-name DJs, by the way – a token hundred or two to cover expenses is standard.

But most concerning is that the same “pay to play” bind extends to the many smaller, upcoming bands that Glastonbury is famous for. It’s romantic to think that a hitherto unknown group might become a breakout star of the best festival in the world, but the route to getting there is becoming more and more exclusive by the year.

One manager told me his bands were offered £250 to play The Other Stage and, in a very typical Glastonbury scenario, they weren’t even offered enough tickets to cover the whole band. Because, for upcoming bands, “pay to play” can literally mean having to buy your own ticket to perform at the festival of dreams. For reasons that objectively seem baffling outside the Glasto bubble, it’s common that individual stages aren’t given enough ticket allocation to book as many bands as they need. That’s what multiple sources report being told in their approaches from bookers. It’s fine if you’re a two-piece, but if you’re an eight-person band, you’re stuffed.

To get around this, some acts might play multiple unpaid or low-paid gigs on different stages, just so they can get enough wristbands for all members. If they finally get in, they’re almost always taking a loss by still having to pay hundreds to physically get their gear there and to feed themselves. “I’ve stopped accepting any offers on principle,” one manager (who, like many who contributed to this piece, wished to remain anonymous) told me. “My artists end up in debt if they play.”

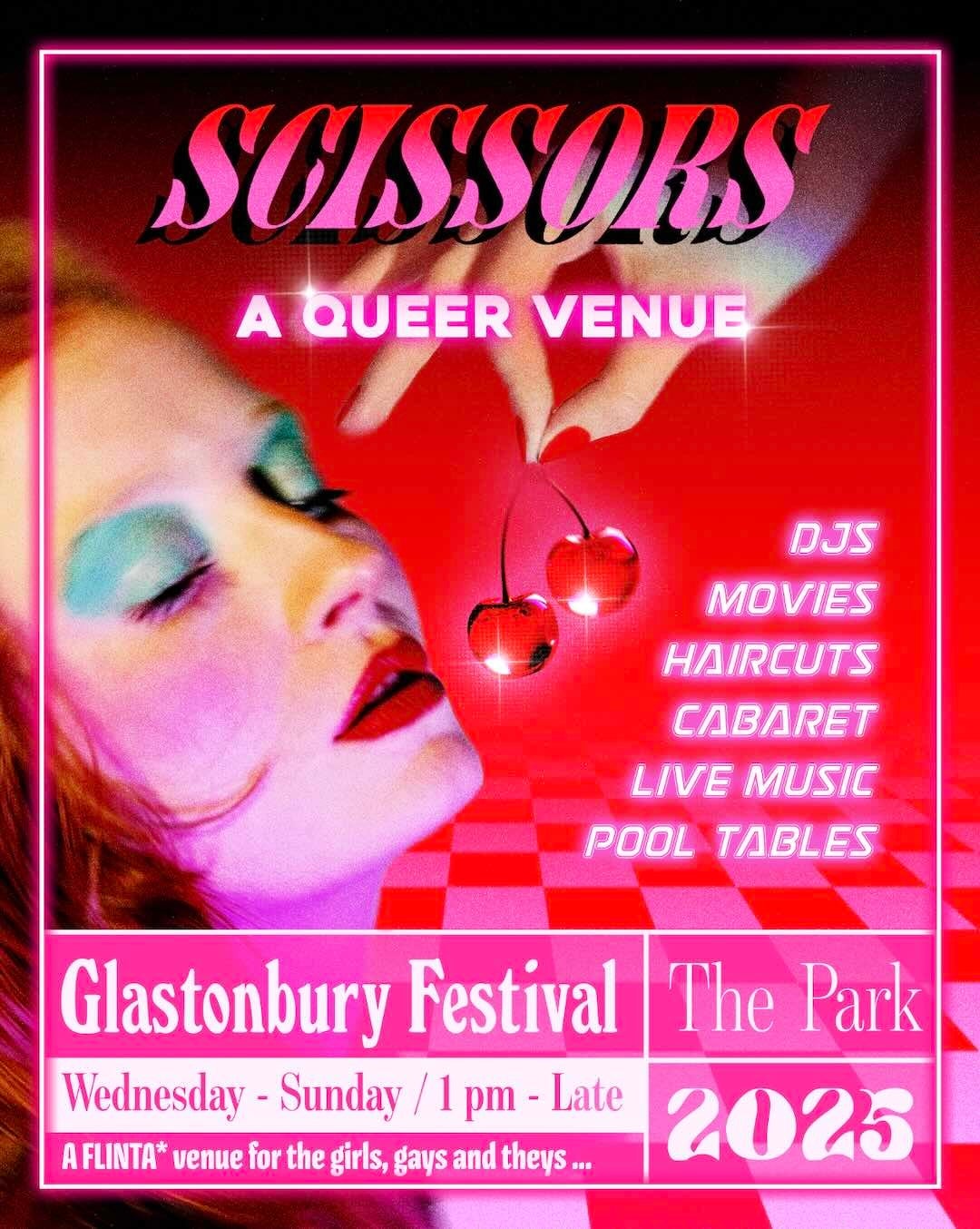

It’s one thing for a mid-level act to “take a hit” financially. But if Glastonbury 2025 was truly levelled-up, attendees would be served pints by Rod Stewart and Charli XCX. Amazingly, one venue on the Glastonbury lineup is not only unable to pay a fee, but is also asking its performers to work three eight-hour bar shifts as well – also unpaid – in order to have the chance of playing Glasto. To make it more awkward, the venue – Scissors – is a new-ish space designed to promote young femme-queer acts. While the festival wishes to make clear that Scissors is one of many venues – such as Arcadia, Silver Hayes, Block9, The Glade and Avalon – that are run independently of the festival, it is located in The Park arena, a central area on site, and listed as part of the official Glastonbury programme. Glastonbury Festival only book five stages directly in-house: Pyramid, The Other Stage, West Holts, Park Stage and Woodsies.

Scissors is a response to the idea of festival bills being perennially male and stale. Outwardly, the festival gets to look cool, progressive and radical. Yet, as stated perennially by institutions such as Oxfam – a key Glastonbury partner – women are subjected to far more unpaid work than men across a lifetime. Making a female-identifying lineup work unpaid off stage just so they can work unpaid on stage is clearly a misstep.

Discounting the unlikely presence of Fatboy Slim’s DJ son, Woody Cook – who identifies as a man – the acts on the Scissors bill are all excellent DJs and performers, who might earn anything up to £1,000 on a regular weekend. Here they’re working for online clout, the chance to post an “I’m Playing Glastonbury” banner and not much else (many acts I spoke to reported feeling a sense of internalised shame, taking in big online love whilst not disclosing the financials). Scissors is a genuinely laudable project, staffed from what I can tell by a dedicated and conscientious team. But the bind they’ve been put in by Glastonbury’s management – of desperately trying to leverage free work – points to a serious blind spot at the top. “They’re treating emerging artists like trash,” one act told me. A spokesperson for Scissors claimed: “Our organisers have approached people and offered a position on the bar staff volunteer programme. They have then discussed that as a secondary offer, they could perform during the festival.”

The dead hand of unpaid work is sadly a constant in multiple other Glastonbury jobs, away from the spotlight. The people that make Glastonbury happen are – from my investigations – also paid either little or nothing. Bookers for key stages might do weeks of work securing big-name lineups for, at most, a couple of hundred pounds. Some do it just for a ticket, with no expenses paid. Working unpaid overtime to build stages and sets to schedule is reportedly the norm. People will be tethered to their venue all weekend, with no chance to enjoy the festival at large, for no money. Festival producers will work insane hours for maybe £150 per day. I’ve worked annually at festivals since 2008 and it’s important to stress that at every other UK festival I’ve experienced, festival production work comes with a proper, take-home pay packet.

Critics say bluntly, “Well, nobody’s forcing them”. But test that logic and there is simply no Glastonbury any more. “Unsustainable” is a word used a lot in private. Backstage at Glastonbury’s venues, the vibe is most certainly veteran. Many diehards – who started in a more blithe era – have done the same roles for between 10 and 20 years. It’s foreseeable that many will retire soon. Less foreseeable is how a younger generation, more attuned to a sense of self-worth and born in a perishing economy, will ever want to step into these unpaid roles. The only logical path is for Glastonbury work to become the sole preserve of those financially blessed to do it. Just as rising ticket prices have edged out working-class attendees, it’s impossible to imagine a new generation of working-class arts professionals coming up through the Glastonbury ranks.

Even if you’re not a festival insider, there have been hints that Glasto isn’t as supportive of its workers as you’d expect. In 2017, a performer committed a physical assault on a Glastonbury worker, which later went to court. In bars and clubs with ID scanners, it’s common for venues to permanently ban people who assault staff – in part, to show solidarity with their workers. Glastonbury, however, doesn’t appear to have this same belief. That same performer is playing this year’s festival. Another incident in the same year saw the festival accused of exploiting around 700 European workers – people who were hired to pick litter on zero-hour contracts and then ditched after earning just two days’ wages. We like to buy into the myth that everyone working there, including litter pickers, is a happy-go-lucky music fan just earning their ticket. Yet the reality of 700 stranded migrant labourers is just as real. It’s frankly sad that none of the long list of left-wing icons who grace cosy panel discussions each year has ever called this out, nor the mass use of unpaid labour. I heard a story about a group of textile artists who pitched making a banner for an area whose theme that year was “anti-capitalism”. The banner was to read: “We Didn’t Get Paid to Make This”. It was rejected.

At a management level, Glastonbury feels like a mystery. A million rumours swirl, but as an independently owned event, it’s within its rights to be coy about its economics and structures. In response to this article, Glastonbury Festival told me that “in terms of fees for professional crew directly employed by the Festival, we make sure everyone gets paid at least minimum wage. We also pay all the performers we book directly for the main stages and we have, in recent years, been working with our dozens of independently-run areas and stages to ensure that bigger budgets are available specifically in support of emerging acts”. Yet, the fact that venues like Scissors and many more are deemed “independent” – despite being centrally located and visibly part of the festival – feels odd.

Because of the perennial sense of confusion, people’s take on Glastonbury’s management fits into one of three narratives: they’re principled, they’re chaotic, or they’re simply greedy. I think the latter is too harsh, given that Glastonbury does indeed raise a huge amount for charity. The festival announced in January that it had donated £2m to the NHS Somerset charity and £126,000 to support NHS hospitals in Bristol and nursing staff across the country, while £1.27m went to organisations including the British Red Cross, Oxfam and War Child.

Sadly, I don’t think it’s governed by clear, upfront principles either. Take Scissors, for example: are the acts there to promote femme artistry, or to supply free content and labour as volunteers for a charitable endeavour? It’s not clear. While some volunteer steward teams I’ve spoken to feel engaged knowing exactly which charity they’re raising money for each year, not many feel that do-gooding glow. They just don’t know where the money goes. The lack of clear principles extends also to the wild wage disparities on site. Many have expressed a private wish that organisers would impose a standardised wage, a transparent pay structure or even accept unionisation.

Which leaves the most likely take on Glastonbury to be that it’s a well-meaning but slightly chaotic institution. This was hinted at in passing by Emily Eavis in an interview last week, addressing the huge online backlash around overcrowding at last year’s event. In the interview, she claimed she had asked a meeting of around 250 staff if they thought it was overcrowded, and nobody put their hand up, which feels worryingly out of step with the feedback of their 2024 audience.

Glastonbury is undoubtedly a unique event, yet all the issues above cut right to the heart of a much bigger debate: what do we want from art and culture in 2025? Do we want art that’s sponsored, sustainable yet soulless, or brilliant but financially unrewarding to its creators? I think Glastonbury is currently trying to do it all, and failing. The sad pragmatist in me thinks that one day soon, it will need to come down on one side of the fence. Meanwhile, I can’t deny a small sadness. I used to see the Glastonbury lineup as a meritocracy. But realising that there’s so much “pay to play” involved, that concept seems tainted to me now.