Book Review

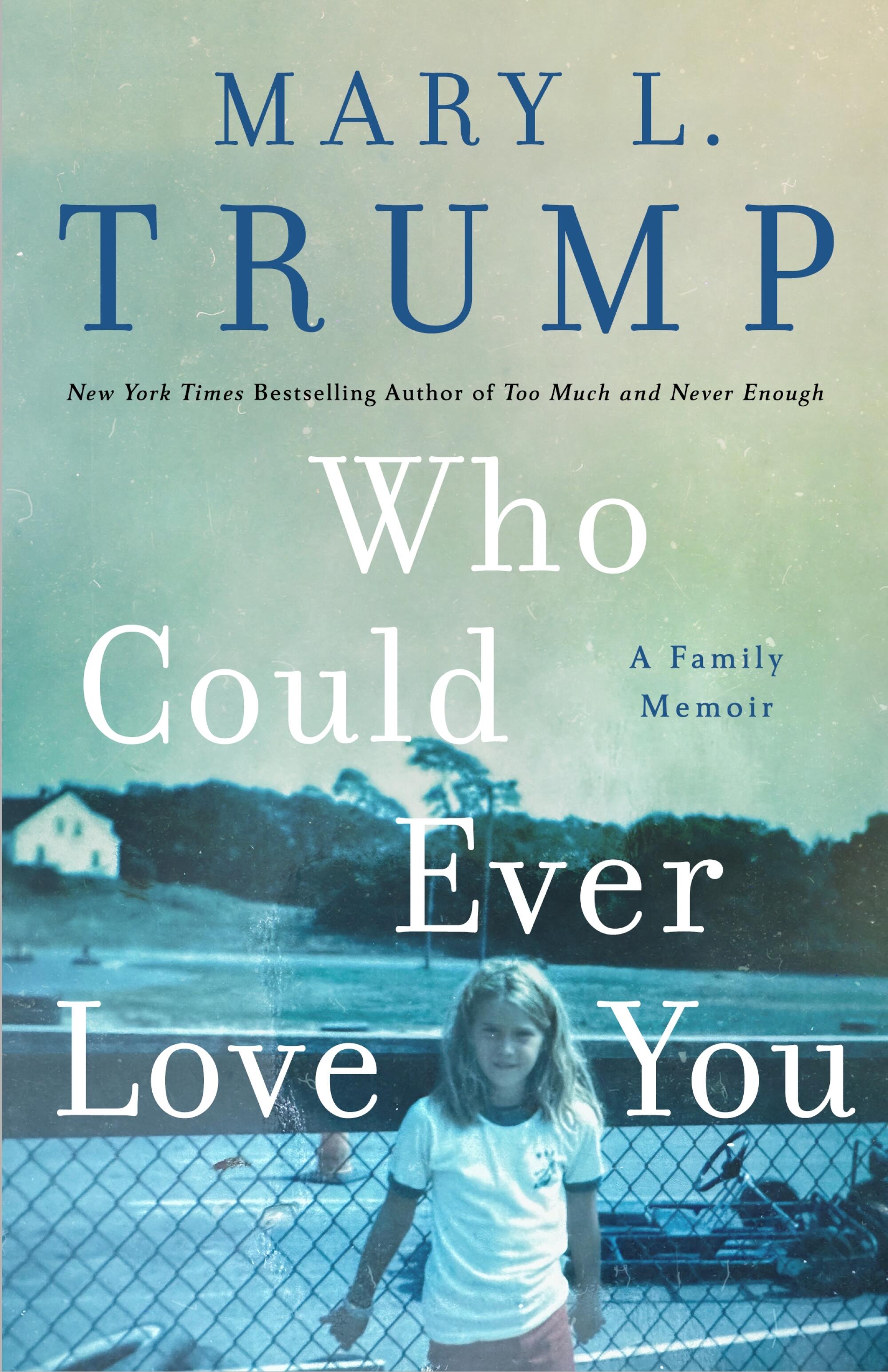

Who Could Ever Love You: A Family Memoir

By Mary L. Trump

St. Martin’s Press: 288 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

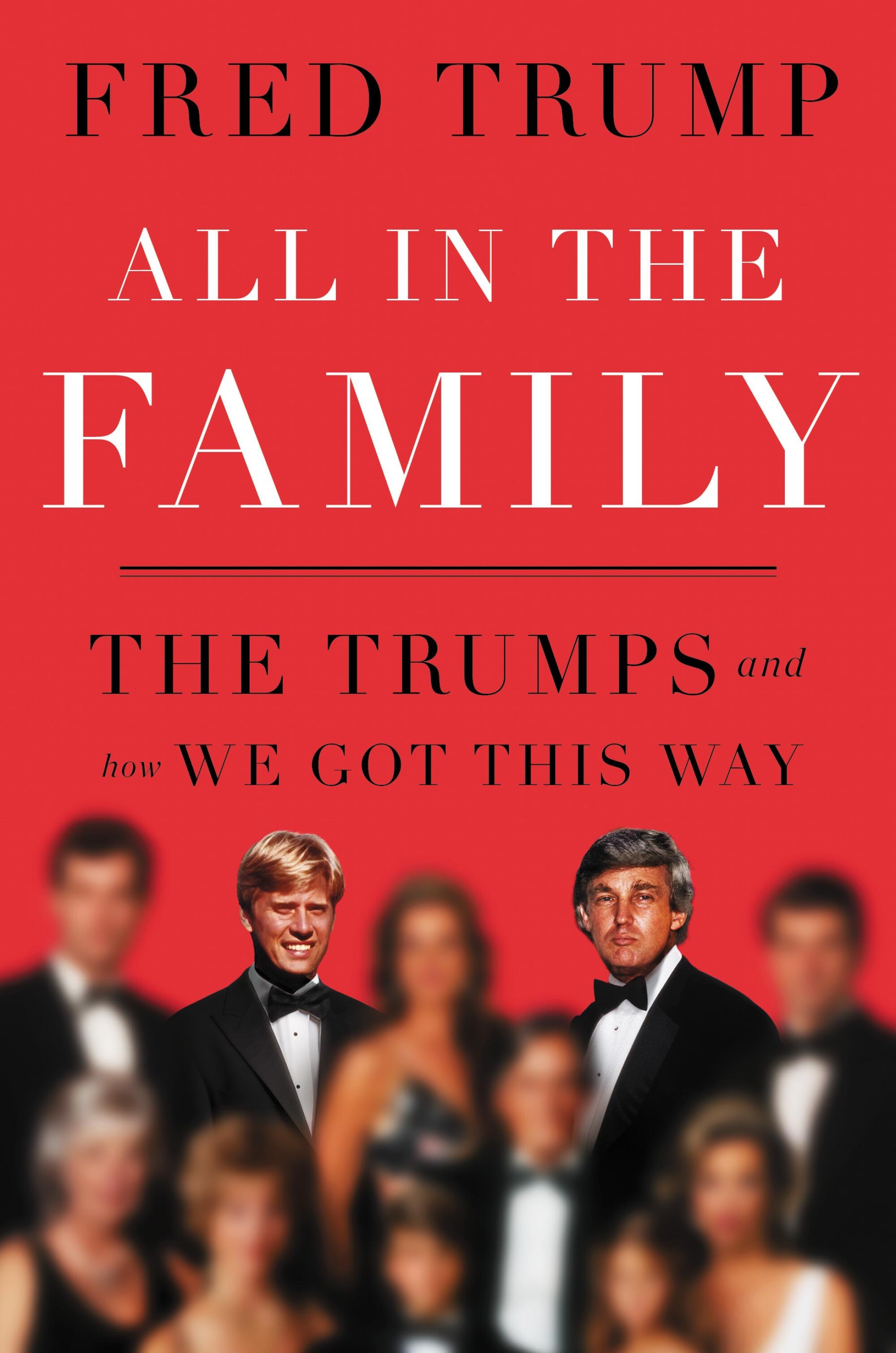

Book Review

All in the Family: The Trumps and How We Got This Way

By Fred C. Trump III

Gallery Books: 352 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Vicious coronary blockages are commonly called widow-makers. Some vicious human beings should be called trauma-makers.

These are the solipsists and sadists who careen through their lives creating psychological carnage wherever they go, laying other lives to waste.

“I’m here because Donald Trump is my uncle,” writes Mary L. Trump in “Who Could Ever Love You,” her unsparing new memoir of the psychological devastation wrought by her family‘s dynamics. As the book opens, she’s in a trauma treatment facility in Arizona, taking a ketamine infusion to ease her despair. The shadow cast by her uncle has become too desolate to bear.

“The Trump name is toxic,” echoes her brother, Fred C. Trump III, in his own new memoir “All in the Family: The Trumps and How We Got This Way.” Without quite as much introspection, Fred chronicles his own Uncle Trump atrocities.

A disturbing number of the stories in “All in the Family” show the former president as much more than obnoxious. He causes, countenances, orders and savors the physical pain of others.

“If this wasn’t evil,” Fred writes of one especially horrific incident, “I couldn’t say what might qualify …. Where did the cruelty come from? I’ve wrestled with this question for years.”

::

These siblings are heavy laden. They are both patients: Mary, as indicated, for trauma, and also dissociation; Fred for alcoholism. In addressing their losses with candor and a measure of self-knowledge, each of them aims to be, as Fred describes himself, “a different kind of Trump.” But neither disavows the name. “Trump” seems to be their gilded cross, and they aren’t ready to put it down. Mary’s memoir is more engrossing than her brother’s, but both books are mostly just very sad.

In tone and emphasis, their stories diverge, sometimes radically. (I flipped with irritation between the books on discovering that the Trump sibs spell their own father’s nickname differently; Mary opts for “Freddy” and Fred for “Freddie.”) But on the tragedy that defined their early lives, they’re in sync. In short, their vile grandfather Fred C. Trump Sr., who died in 1999, joined forces with their even more vile Uncle Donald to drive their vulnerable, if charming, father Freddy (Freddie?) to misery, penury, drink, rehabs, humiliation, more drink and finally an early grave.

It became truly gothic. As their father got increasingly emaciated and sick, his father consigned him to a camp cot in a stuffy attic room and made him work as a janitor. No one visited Freddy in the hospital. Finally, he died alone, in 1981, at 42. His ashes were buried in the family plot, though he’d longed to have them scattered at sea.

Mary Trump

(Avary L. Trump)

In the unkindest cut, when it came time to divvy up Fred Sr.’s estate in the 1990s, Donald worked to effectively disinherit his niece and nephew. Mary and Fred then sued their uncle and his siblings, and Donald went ballistic, not just countersuing but moving to deprive Fred‘s then-infant son William, who is disabled, of much-needed healthcare. It was barbaric.

Mary, who has a doctorate in psychology, is franker than she’s ever been about the emotional toll her family’s savagery took on her. Fred, who comes off as more eager to preserve his privileges as a Trump than his sister, leans into a good-sportism that seems almost sadder than avowed mental illness.

Fred’s book was written with the assistance of Ellis Henican, a ghostwriter for conservative authors and a political analyst on Fox News. In the book’s creepiest passages, Fred magically shakes off his family bruises and pledges his love — of all things! — to Uncle Donald. A political needle is being threaded, to unpleasant effect.

Much of the history in both books is rehash: Donald’s mean-spiritedness, his racism, his trademark abuse of others, his draft dodging. But even learned Trumpologists may be surprised to learn that Freddy, in a dark moment, brought Mary a chunk of horse manure as a birthday present. Donald once ordered young Fred III to hit his Uncle Rob. When he obliged, Rob walloped him back. From Mary’s book we also learn that their overwhelmed mother — by turns oppressed, threatened and banished by the Trump family — regularly ignored Mary’s asthma attacks and refused to take her to the hospital, though she was audibly suffocating. This amounted to a form of torture that haunts Mary.

Fred C. Trump III

(Terry Torok)

The most soul-crushing line in the books belongs to Uncle Donald: “Maybe you should just let him die.” Fred remembers then-President Trump saying this of Fred’s son William, who was then in his 20s. Too heartbreaking.

Reading the two books in sequence, I have to admit I briefly thought: Don’t let Trump see you cry, you two! He luxuriates in your suffering — in everyone’s suffering!

But of course Mary and Fred know this. They just don’t care what Donald thinks or does. Fred is retired, having made a decent living in commercial real estate services; he is sober, contented and devoted to his wife and three grown children. And Mary Trump? She’s a household name in her own right — a regular commenter on politics, the publisher of a popular newsletter and the author of two bestsellers already: “Too Much and Never Enough,” an unauthorized biography of her uncle; and “The Reckoning,” an analysis of the harm he inflicted on the nation.

“Who Could Ever Love You” unaccountably ends with what seems like a series of short takes from a diary kept during inpatient treatment. Mary doesn’t sound hopeful exactly, but she recognizes at last that she has both the moral high ground and the authority (and presumably enough money) to stand up to her uncle as her father never could.

In the end, she writes, “Here we are, Donald and I, still on diametrically opposite sides of everything. The difference now — he’s not the only one with power.”

“All in the Family” has an ending that’s much less heartening.

Throughout, Fred’s memoir is tonally unstable, with the sentence fragments and one-sentence paragraphs characteristic of a prefab bestseller. But sometimes it reaches, scattershot, for a bigger point. These bigger points threaten at times to drag all of humanity down with his own accursed family.

“This nation and this family are inextricably intertwined,” he writes. “As go the Trumps, so goes America.”

If this is true, heaven help us.

Virginia Heffernan is a regular contributor to Wired and writes a newsletter, Magic and Loss, at virginiaheffernan.substack.com.